The Art of (Re-)Making Ruins:

Between the Cracks of Cuban Media of Precarity

Graydon Smith

Department of Anthropology, University of Victoria, Canada.

Abstract This paper considers contemporary Cuban visual media of precarity, from the genres of multimedia photography, performance art, and street art, arguing that they challenge discourses of progress, resistance, and decline to consider alternative futures during ongoing Cuban crises. I contextualize works historically and through ethnographic vignettes from fieldwork in Santiago de Cuba, applying the theoretical lenses of Gordillo’s (2014) rubble and Suárez’s (2014) ruin memory. I argue coverage has traditionally neglected the polyphonic meanings behind critical discourses of Cuban media of precarity. I build upon past visual-materialist literature on Cuban ruination, considering how more recent media reflect new crises, requiring updated approaches to better understand their capacity for challenging prescriptive futures and a romanticized past by re-framing the political weaponization of utopia and dystopia. I conclude the genres represent heterogeneous calls for alternative futures by emphasizing the lived, embodied traumas of infrastructural decay caused by bidirectional pressures, and call for caution in glorifying criticism in a fraught context.

Résumé Cet article propose d'étudier les médias visuels cubains contemporains de la précarité, de la photographie multimédia et de l'art performatif jusqu'à l'art de rue (street art). Ce faisant, il soutient que ces médias remettent ainsi en question les discours sur le progrès, la résistance et le déclin afin d'envisager des futurs alternatifs durant les crises cubaines actuelles. Je contextualise les œuvres d'un point de vue historique et à travers des vignettes ethnographiques issues d'un travail de terrain à Santiago de Cuba, en appliquant les prismes théoriques des concepts de « décombres » de Gordillo (2014) et de « mémoire des ruines » de Suárez (2014). Je soutiens que la couverture médiatique traditionnelle a négligé les significations polyphoniques qui se cachent derrière les discours critiques des médias cubains sur la précarité. Je m'appuie sur un corpus ancien de littérature visio-matérialiste sur la ruine cubaine, en examinant comment des formes médiatiques plus récentes reflètent les nouvelles crises, nécessitant par là-même des approches réactualisées pour mieux comprendre leur capacité à remettre en question les futurs prescriptifs et un passé romancé tout en recadrant l'utilisation politique de l'utopie et de la dystopie comme armes. Je conclus que ces genres représentent des appels hétérogènes à des futurs alternatifs en mettant l'accent sur les traumatismes vécus et incarnés de la dégradation des infrastructures causée par des pressions bidirectionnelles. Dans un contexte tendu et plus nuancé qu'il n'y parait, j'appelle à la prudence dans toute tendance à glorifier la critique..

Keywords Cuba; media; crisis; ruins; memory

Cultures go to ruins, but after, they come back to life in images, rekindling the embers of the ruin’s spirit. The image intertwines with myth as cultures form, preceding them and following their funeral procession. It favours their initiation and their resurrection.

José Lezana Lima, The Image of Latin America

Alcántara during his live-streamed performance. Photo credit: Memory of Nations, 2020.

In early January 2020, three young Cuban girls lost their lives in the Jesús María neighborhood of Havana when a balcony collapsed on them. The structure was slated for demolition, but locals claim this was indefinitely halted. The tragedy, one of many across the city, prompted a livestreamed performance by Cuban artist Luis Manuel Otero Alcántara, who walked with a construction helmet that read: “children are born to be happy, not to die in derrumbes [collapses]” (Manuel Alvarez 2020; Martí Noticias 2020). Soon after, he was arrested for the act, highlighting the state’s fear of foreign media covering its decaying infrastructure in new ways. Fatal collapses in Havana’s aging buildings have only increased over time alongside amplifying precarity since 2020. While Cuba does not officially publish statistics (Eaton & Lewin 2018), media reports document numerous fatalities annually, with many more injured (Buschschlüter 2023; Normand 2023; CiberCuba 2024, 2025; 14yMedio 2024, 2025a, b; Moya 2025). As Cuban author Lezama Lima (1972) notes, Cuba’s culture has endured many threats, signaling ruin across eras. Yet, he adds, images rekindle temporal rhythms of the past, both productively and harmfully. In visual media, Cuban creatives like Alcántara gaze back at the ruin, challenging preconceptions to signify both mourning and regrowth.

Precarious Narratives: The Temporal Rhythms of Ruin Memory

As I will argue, artists redefine the use of ruination in Cuban iconography, reshaping a legacy of romanticization of infrastructural decay. Following Gordillo (2014) in rejecting ‘ruins’, I engage with Stoler’s (2013) work on ruination as dynamic and ongoing to reflect on a tired narrative, once popular within visual-material studies, of ruins’ discursive and ideological associations. It is increasingly urgent within a worsening economic and migration crisis that has disrupted Cuban lives in ways once thought unimaginable (Boudreault-Fournier 2023). As infrastructural challenges increase, they haunt everyday thought and inform visual media. Ruins are being remade from highly potent historic indexes, associated with emotions, time, and romance, throughout centuries of obsession by so-called ‘ruinologists’ (Unruh 2009). Here, I consider media of Cuban media of precarity in multimedia photography, performance, and street art, key genres engaging with precarity, returning ruinologists’ gazes with alternative visions of ruins remade.

Their works challenge common imaginaries of Cuba, led by aging cars, tropical scenery, and ruined buildings. Like Suárez, I urge readers to remember “that the crumbling preceded the Cuban revolution”, including in Cuban media (2014, 44). Foreign attention grew after the Soviet Union collapsed, as Cuba’s severe economic crisis forced the state to readopt tourism. Visitors flocked to a forbidden paradise behind an iron curtain, returning with stories of a lost past in romanticized, colonial buildings. The use of ruins was personally nostalgic, but also politically useful within a persisting “economic and ideological scramble for the island”, shaped by globalization, ideological friction, and Cuban exceptionalism (Dopico 2002, 451). Ruins are listed as a key area of materialist studies in Cuba by Cabrera Arus (2021), who argues that most scholars have challenged foreign preconceptions of romanticized ruins. Yet, despite increasing collapses, most visual-material scholarship reflects earlier crises and foreign media (Dopico 2002; Quiroga 2005) with notable exceptions (De Ferrari 2020; Boudreault-Fournier 2021). I argue that within this ideological scramble, academics should be cautious when interpreting Cuban creatives’ political goals, as the state increasingly labels artists as dissidents, causing state violence and jail time (Foucher 2024).

In this paper, I reflect on recent Cuban media with themes challenging this typecasting of Cuban life, refracting ruins and their memories to signify many citizens’ changing values. I engage with ideas of precarity—common in Cuban visual-materialist studies—linking ideology, danger, and the possibilities of eras and their dreams, where material reality, scarcity, and loss resonate (Garth 2020; Sklodowska 2021; Loss 2021; Boudreault-Fournier 2023). I apply theories from studies of ruination and its aesthetics to counter romanticized, picturesque portrayals of ‘ruins’, which are often lived in. Following Unruh (2009), I argue that Cuban structures commonly labelled as ‘ruins’ are lived-in spaces; they are not static, but part of how humans navigate uncertainty. I draw primarily from anthropologist Gastón Gordillo (2014) to reject ‘ruins’ in favour of terms like ‘rubble’ to evoke ongoing ruptures and lived impacts. I reflect on recent Cuban media that reinterprets Lucia Suárez’s work on ruin memory, building on her analysis of Cuban counterpoints to ruination in the 1990s and 2000s. These frameworks help decode media of precarity[1] to look beyond romanticized ‘ruins’ and learn from the traumatic memories held within them. I argue the works combat simplistic tales of resistance and decline, showing how the fears of life in crises are embodied for those living amid decay.

Notions of precarity and resilience are common threads in contemporary literature on Cuba, which has navigated cyclical crises for decades (Boudreault-Fournier 2023). Precarity has been studied in the Cuban arts by De Ferrari, who describes it as “structural violence that prevents humans from reaching their full potential”, forming “the root of contemporary art production on the island” where Cuban “[l]ives coexist with brokenness in mutually constitutive ways” (2020, 546). These notions provide a locally contextualized example of Anna Tsing’s definition of precarity as “that here and now in which pasts may not lead to futures” (2015, 61). I argue that visual media of precarity help problematize the ruin as a lived in space (see Unruh 2009; Gordillo 2014), through works that are not stuck in the past, but tied to ongoing, embodied, and affectual experiences within a flurry of emotions, memories, and strategies. It reflects la lucha (the struggle), a frequent theme where Cubans bond over shared strategies for adversity, described by many others (i.e. Garth 2020; Boudreault-Fournier 2021, 2023) and in my own work (Smith 2024).

As ongoing spaces enmeshed in the past, present, and future, I consider ruins using Gordillo’s (2014) notion of ‘rubble’. He applies ‘rubble’ to problematize the historical obsession with the ruin in both academia and visual culture, as decaying structures impact human lives. Rubble can also reflect the loss of homes or even lives. Likewise, in Cuban media, practitioners use rubble as a commentary on material shortages and ideology as both inspirations and limits. Works reimagine precarity and decay through reality and fiction, invoking alternative pasts, presents, and futures, commonly considered to evoke either reparative futures or the death of a romantic past now relegated as a commodity for foreign enjoyment. Ruins reflect a viscerally painful part of contemporary life in Cuba as citizens weather a devolving, ongoing economic crisis, with inconsistent acceptance by the state, increasing disillusionment, and foreign pressure. By remaking ruins and amplifying their persistent memories, one can push back against foreign cooptation of the aesthetics of precarity, demonstrating local agencies, engagements, and entanglements that index the possibility of change.

Storied Ruins: From Yesterday’s Dreams to the Afterlives of Rubble

According to Quiroga (2005), Cuba is perhaps the prime example of a global obsession with ruins, driven by ideas of nostalgia. Writing about the capital Havana, Quiroga writes: “collapse somehow allows the city to levitate in pictures” (2005, 81).[2] In this section, I respond to these foreign framings, using ethnographic vignettes from fieldwork in Santiago de Cuba to present Cuban counterpoints which help contextualize the genres discussed in the paper and reinterpret them to emphasize the past and failure. These metaphors of lost dreams, to some, reflected their own nostalgia, and to others, the loss of the Revolution’s utopian promises. Cuba is thus succinctly described by Dopico as a longtime “projection screen for Northern fantasies” (2002, 456). The current generation in Cuba, with whom I have done fieldwork, has grown up in the wake of this foreign framing of a cyclical Cuban collapse that has never arrived (Boudreault-Fournier 2023). Since the 1990s, with growing attention to Cuban ruins, many scholars have published responses to the use of ruins in foreign media and, to a lesser degree, in Cuban art. Works on the latter topic, perhaps optimistically, resist narratives of failure and staticity by centering Cuban agencies in maintaining decaying structures (Unruh 2009; De Ferrari 2020).

This perspective was mirrored in my own research. Participants reflected on these themes in varying ways, echoing Boudreault-Fournier's stance that “despite the severe anxiety and distress associated with housing, construction and renovation also give birth to vibrant stories of hope and achievement” (2021, 230). This duality resonates with experiences shared by a Cuban friend who said that the current crisis has been the hardest time for her since the damage to her home in Santiago de Cuba when Hurricane Sandy made landfall nearby in 2012. She had felt alone in procuring materials for repair; government resources were minimal and allocated, she noted, to the most disadvantaged and urgent cases, forcing families to compete for funding. While storm damage to her colonial home remains, she has managed to maintain it in a fragile state. [3] She added that friends and neighbours who received remittances from family abroad reflect a new class divide, being more likely to have renovated homes (see Garth 2020; Smith 2024, forthcoming). These fears persist as storms and weather damage increasingly cause collapses (Boudreault-Fournier 2021), while, elsewhere, in Havana, citizens complain of repairs being prioritized for hotels and the tourist gaze (Dabène 2020; 14yMedio 2024).

These anxieties and their foreign counterparts are best understood through Suárez’s ruin memory, developed to reflect the dynamic use of ‘ruins’ in Cuban media during crises. These works deconstruct “how the city is survived by locals, exoticized by tourists, and reconstructed by the imagination…to think about the ruins and those living in them” as “more than a depiction of the past or what has been lost” (2014, 38). As I will argue, ruin memory helps decode Cuban media of precarity, encouraging viewers to think beyond expected narratives for the future where contemporary artists are often framed as anti-Revolutionary. Engaging with these works, it is important to attune to both the possibilities and the violence which reverberate in decaying spaces.

A collaborator and I entering the building described below. Photo credit: Anonymous Collaborator (2023).

During my fieldwork in Santiago de Cuba, a photo-walk led me to consider more viscerally the afterlives of more recent ruins when an artist suggested photographing the skeleton of a building. He explained the building was left by an emigrant, and the materials had since “disappeared”. Despite being labelled a ruin by my Cuban collaborators, it exemplifies what Cuban artist Carlos Garaicoa calls “ruins of the future” (in Kovach 2016: 76), or remnants of plans halted by material scarcity, that offer “a more complicated narrative of Cuba’s modernity, in which tentative construction plans represent empty promises of economic growth” (Kovach 2016, 75). Despite its choice as a set-piece for conceptual and documentary photography for a collaborative research outing with the curator of a local visual museum, it contained afterlives as a property that could be pieced out and occupied. As Gordillo (2014) argues, ruins are not frozen despite visual illusions to the contrary. This, I argue, is addressed in Cuban media, where techniques of layering and manipulation challenge temporality, and where the affordance of the moving image has been used as a set-piece for alternate futures.[4]

As we left the structure, cameras in hand, two ladies approached Demian, my principal collaborator, who was also the museum’s director.[5] Upon hearing laughter from the group and inquiring, Demian explained they’d asked if he could give them the property, thinking we were state workers in charge of distributing leftover properties from internal or global emigrants. In the work produced and the artists’ framings, these buildings became stand-ins or metaphors; they indexed the hauntings and losses felt by living through the crisis. I was led to consider how these understandings may not reflect the complete reality of their abandonment and the other forms of survival which they index. As Suárez argues, discussing ruin memory, foreign and solely visual obsessions with Cuban ruins put “us at risk of being blind to human suffering” (2014, 51). Thus, by freezing time, we may allow suffering to continue. However, it is important not to forget that this image is not just one of powerlessness against a foreign gaze. As I argue, Cuban media looks back at this gaze. Like the romantic colonial architecture of Cuba, with its traces of painful memories of slavery and colonialism (Boudreault-Fournier 2021; Gabara 2006), buildings serve as material containers of violent legacies that continue to haunt, regardless of visual appeal.

Soluciones de Mampostería (Masonry Solutions, author’s translation). Photo credit: Lucia (2023).

The afterlives of ruins extend to both residential and state projects, as discussed in two photos submitted for the project with the museum by Lucia, a photographer and social media influencer. The first depicted a colonial home dating back hundreds of years, near where I had been living, captured on the way to grab water bottles during another photo-walk. To Lucia, it was deeply beautiful, but tragic: everyone valued the beauty of structures they could not afford nor source materials to repair, especially to support generational families inside, creating friction. Another, shared during a museum event, showed a once-promising factory’s abandoned bridge.[6] She described the image as “conceptual, or maybe documentary [photography], because soon, the building will no longer be, or remain, there, as it no longer works.” She groups it with many projects that reflect utopian dreams on the island, “vital works” that mysteriously vanished from official discourse but haunt the public imaginary. She debated if they would be finished, and if so, if they’d be productive or solely propaganda.

These discussions call to mind the work of Gandy (2022) and Tsing (2015) on temporality, ruination, and growth in the wake of progress narratives, and the lives contained and excluded by them. In their discussions on ecological spaces, new life does not neglect the death of old ways of life. They are sites not only for romance, but mourning. I follow Tsing’s call to attune to new temporal rhythms emerging amid contemporary entanglements that escape the expected marching pace of utopian futures (see also Pels 2015), much like Cuban state narratives. She prompts us to imagine other forms of growth, cooperation, and creativity outside of preexisting molds, while confronting the lives that cease after violence. Cuban futures do not need to occupy expected forms, an argument made by myself (Smith 2024) and others, reflecting a shift from post-Soviet transition studies (Powell 2008; Roland 2010; Suárez 2014; Price 2015; Garth 2020).[7] In ‘ruined’ spaces, Gandy argues, “[i]maginative interventions by artists...remind us that looking, thinking, and representing the familiar in an unfamiliar way can...be a kind of radical cultural and political praxis” (2022, 113).

Reframing Ruins: Layering in Cuban Multimedia Photography

I build upon scholarship which has employed ruins to discuss identity and past crises with multimedia and conceptual photographs primarily by Carlos Garaicoa (De Ferrari 2015; Kovach 2016). Multimedia pieces[8], like other genres discussed, use ruins as canvases to interrogate memory and discourse, reflecting Quiroga’s (2005) work on the Cuban palimpsest. Kovach notes how Garaicoa’s work occupies the divide between ruin/utopia, with work “intertwined in tourists’ exotic imaginings” and past “narratives of oppression and dreams of modern progress that together fueled revolutionary ideology”, thus, arguing it “mythologizes metaphors of Cuban resilience, and destabilizes the historicity of Cuban modernity (2016: 73).”

Above: Dyad: Sin Titulo (Trotcha Perpsectiva).

Below: Detail. Artwork Credit: Carlos Garaicoa (2022). [9]

Garaicoa’s work exists in contrast, or opposition, to the popular illusion of Havana described by Dopico as a “consumable geography that symbolically abolishes everything else around it” (2002, 453). He developed the series, hoping to remake Cuban ruins as a new form of visual index and challenge the emerging metaphors of a post-restriction Cuba, where the state had once tightly controlled its visual image. He intended the work as a counterpoint to foreign media (which overshadowed Cuban art) and commoditized either an exotic paradise or a heterotopic socialist experiment.[10] The series exemplifies a Cuban counterpoint to what is critiqued by visual tourism studies, using concepts like the ‘Caribbean picturesque’ (Thompson 2007), the ‘politics of the picturesque’ (Sheller & Urry 2004), and the ‘tourist gaze’ (Urry 2010).[11]

This growth in attention led to other popular literature, with Cuban ruins peaking in popularity in the 2000s. Quiroga (2005) has argued that few foreign uses of Cuban ruins offered critiques of the socialist state, employing them instead as detached metaphors for nostalgic viewers that ignored human lives within them. This is juxtaposed with Cuban counterpoints like Garaicoa, which offer urgent commentary on modernity, progress, and temporality, implying the “unmooring of the radical utopian underpinnings of revolutionary ideology” (Kovach 2016: 75), complicating narratives of Cuban modernity amidst increasing uncertainty.[12] Garaicoa describes walking in Habana Vieja, a UNESCO heritage site, to witness “an abandoned past” of a revolutionary dream that “[causes] us to feel the total absence of a model for the present”. He adds that his art is “associated with the creation and fantasy of a different reality” (in Suárez 2014, 44). His description of lost dreams links to Quiroga’s stance that Cuban media of precarity shows “a world in which possibilities of the future have ceased to become the merchandise” (2005, 100). He expresses that his works directly oppose the foreign preoccupation with Cuba as a dying dream, critiquing this framing’s use of racialized metaphors, something extended by other scholars (Suárez 2014; Lane 2010). In rejecting these frames, he exemplifies how Cuban creatives perceived an era where the profitability of Cuban media rose with inconsistent economic benefits for locals.[13] As I argue, artists in Cuba offer diverse sentiments and predictions of the future. Some explicitly ascribe to state, foreign, or tertiary expectations, while others like Garaicoa, offer a more ambivalent stance (Price, 2015).

Cynicism over the loss of past dreams is frequent in Cuba, something exemplified by Garaicoa and his dyadic approach, challenging their perceived inevitability. My main research collaborator, poet, and artist, Demian Rabilero, described his childhood visions of Cuba resembling a utopian, Star-Wars-like future where Cubans would have technological cities and advanced space travel. His visions of future grandeur that never arrived mimic those of Garaicoa, who layers architectural plans to imagine futures as otherwise, commenting on both “ruin and utopia, which have long figured differently in local and foreign perceptions” (Kovach 2016, 73). Describing structures like those I photographed in the prior ethnographic vignette, Garaicoa describes his ‘Ruins of the Future’, halted or abandoned projects growing in number, where:

idyllic and nostalgic ruins...coexist with the ruin of a frustrated political and social project. Unfinished buildings abound, neglected and in a sort of momentary oblivion. The encounter...produces a strange sensation; the issue is not the ruin of a luminous past but a present of incapacity. We face a never-consummated architecture, impoverished in its lack of conclusion, where ruins are proclaimed before they even get to exist. (in Kovach 2016, 76).

A close parallel to Garaicoa’s work is Cuban-American artist Humberto Calzada, who paints liminal, magical, realist ruins. In recent years, he began layering them on photographs in diasporic collaborations with Habanero photographer and street artist Hector Trujillo and Cuban-American Victoria Montoro Zamorano. The result imagines a lost, colonial future. He describes his ruins without idealism: “if you look closely, there is also a bit of sadness sometimes and loneliness…I think that you can express that through beauty [and] ugliness” (in Bosch 2008, 21, 25). His works allow him to imagine a better Cuban childhood through the rebuilding of ruins, within a growing trans-diasporic movement (Herrera 2011; Duany 2019). Both artists exemplify Cuba’s evolving visual language, increasingly multi-genre and manipulated to unfreeze time, replacing violent framings with “aesthetic openness against what is perceived to be a stagnant political reality” (De Ferrari 2015, 5).

Calzada de Luyano y Calle Ensenada. Artwork credit: Calzada, on photo by Trujillo (2022).

Following other pieces which link embodiment with material decay as a symbol of Cuban crises, De Ferrari argues that Garaicoa views Havana “like a body in distress” and the “peeling surfaces of the old buildings as troubled skin”, thus decrying Cuban ideology’s slow death (2015, 11). His use of ruins to call attention to distressing times is reminiscent of the ongoing urgency and remaining potency of ruins I encountered in fieldwork. Alongside examples published elsewhere (Smith, forthcoming), one photographer, Luís, shared a photo, Peligro! [Danger!] (see Smith 2024, 107). He felt the government anticipated derrumbes, hoping passersby would not be underneath—something he feared—but would only provide repairs afterwards. This echoes the concerns of Alcántara in the piece that opens this paper. They reflect an increased urgency which may make it harder to romanticize Cuban ruins.[14] Meanwhile, mainstream media increasingly applies images of Cuban ruins to illustrate a predicted political collapse (i.e. Otix et al. 2023). I argue academic coverage must emphasize the gaze staring back, a Cuban counterpoint, both documenting and challenging precarity. De Ferrari notes this counterpoint, juxtaposing “reality and sublimation...to render more evident the distressing living conditions of Cubans today” (2015, 235). I argue Cuban ruins are no longer an “artistic cliché” (Unruh 2009, 197) but canvases for change, challenging the staticity of ruins that hold infrastructural dangers as described by Luís. Many artists frame their work in opposition to discourses that sanitize collapses, despite the growing number of deaths caused. They resist frames that Quiroga argued hid “atrocities in the ruined city” to not shock viewers seeking an aesthetic and “dignified...poverty of resistance” (2005, 81).

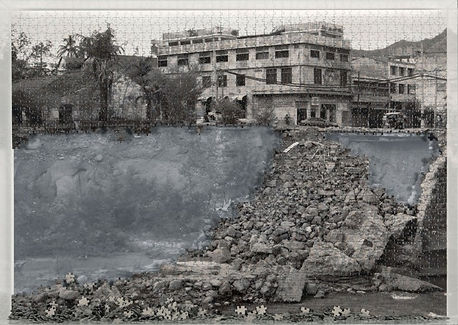

L: Honda (2022) [Puzzles Series] by Carlos Garaicoa. R: Detail. Photo credit: Garaicoa (2022).

Garaicoa’s work perhaps best exemplifies Gordillo’s (2014) stance that demolished buildings remain in memory by superimposing lost structures over their remnants. It exceeds genre classification, using many formats to show the afterlives of rubble, like remaking ruins and demolitions into puzzles and other items. Applying mixed media— strings, organics, bullet holes, and puzzle pieces—he confronts violence, utopic dreams, and the role of memory in letting ruins linger (De Ferrari 2007, 2015). He has lamented that his work is often appropriated for simplified narratives as the art market limits his ability to exhibit for, and impact, Cubans (Fernandes 2006; Cepero 2019). Like Quiroga’s Cuban palimpsest, his work “does not reproduce the original, but...dismantles it, writes on top of it, [and] allows it to be seen” (2005, ix).

Ruínas (Ruins) by Carlos Martiel (2015). Photo credit: Martiel (2015).

Performing Under Rubble: Performance Art and the Discomforting Gaze

Performance arts in Cuba are a clear example of my argument that Cuban media of precarity can help decode uncertain futures, without following preexisting molds like a transition to neoliberal capitalism. The genre has drawn comparatively higher academic attention (Fernandes 2006; 2020, Fusco 2015, González Álvarez 2022). It includes some of the earliest engagements of ruins and rubble in Cuban media. I analyze pieces by Carlos Martiel, Henry Eric Hernández, and Luis Manuel Otero Alcántara to consider the intersections of bodily autonomy, violence, and the power of rubble. Performances typically engage with urban spaces, addressing how challenges of life in precarity hint at possible lives otherwise. Historical engagements between performance art involving burial and rubble highlight the violence of temporal decay entwined in networks of power. Some of the earliest engagements with rubble in Cuban performance arts come via Ana Mendieta, whose work included self-burial within rubble, amid her broader Silhouettes series. Despite inconsistent coverage, her engagements are the most documented of the era. Others, like performances where Lazaro Saavedra and Abdel Hernández were buried in rubble, are scarcely remembered beyond photos.

Cuba’s famed performance arts gained traction in the 1980s, emerging in response to material scarcities as artists elected to use their bodies and the urban social milieu to resolve them (Fusco 2015), while spreading their messages. According to performer Leandro Soto, “that’s how we made our art in Cuba... there were no materials, so we were forced to use our creativity and inventar” [invent] (in Herrera 2011, 38). This led to urban space, including decaying structures, as an artistic venue, and the most influential early collective was named, tellingly, ArteCalle [ArtStreet] (Fusco 2015); they developed cultural expressions out of scarcity and urban decay. Other collectives soon followed in Cuban performance art’s golden age, where the state allowed more critical expression (Camnitzer 2009). Nonetheless, critiques were arguably limited to what was useful politically (Fernandes 2006). Other groups like Arte y Derecho [Art and Rights] are neglected academically, per Cuban artist and visual anthropologist[15] González Álvarez (2022), with controversial performances leading to repression, beatings, exile, and imprisonment, which is seldom reported.

Kermesse to Disillusion (2001), Henry Eric Hernández.

Photo credit: Hernández (in González Álvarez, 2022).

By the 1990s, many artists began to engage in more symbolic work to avoid repression as the state sought to maintain its fragile national hegemony (Fernandes 2006; Fusco 2015). For some, themes of precarity provided an avenue, and critical work became an undercurrent, like Tania Bruguera, whose performances using violence and ruination indexed the death of past narratives, including 2007’s Trust Workshop.[16] Less overt artists like Henry Eric Hernández designed participatory art projects meant to symbolically heal trauma from unfair burials caused by state power, with less overt tactics in terms of public engagement, compared to the confrontations of Arte y Derecha or Bruguera (González Álvarez 2022). Nonetheless, his work was provocative, using human remains consensually to redefine memories and the traces of death. Hernández’s goal can be tied to Gordillo’s discussion of the material traces of violence through rubble beyond abstract thought, viewing corpses as “the rubble of human bodies” (2014: 190).[17] In Hernández’s work, the exhumation of corpses with family permission allowed for processes of healing tied to memory and reconstruction. His works sought to subtly correct state power that had traditionally diminished or erased narratives in which certain groups, for example, average, non-heroic citizens, and religious leaders, were not met with the same opportunities, even after death.[18]

Similarly, the marking of violence on bodies as a result of material and political projects, both internal and external, can be seen throughout Carlos Martiel’s performance art. He regularly uses his flesh as a queer Afro-Cuban to comment on the violence faced by marginalized groups both in Cuba and its diaspora, as well as other nation-states, following a trend in Cuban art (De Ferrari 2015). Throughout his career, many of his performances have included rubble being placed on his nude body for extended periods.[19] His work interrogates legacies of racism and slavery, such as Muerte al Olvido [Death to Oblivion, author’s translation], where he crushed a marble replica of African folk art from his ancestors’ culture, which he had only relearnt with a DNA service. Ruins (2015)[20] had white gallery visitors cover his nude body until he was no longer visible, reflecting on the rubble of racialized violence. Further work applies rubble varyingly as a sign of foreign ancestral memory and violence, such as in Uruguay with Ascendencia Charrúa [Charrúa Ancestry], or in Mexico, where a concrete vessel is hammered open to reveal his body by local Afro-Mexicans, and in Reconocimiento [Acknowledgement], standing in rubble of a box that could not contain him, ending a cycle of violence.[21] These pieces reflect uses of transgression in Cuban art described by De Ferrari, who writes “when the human body is cast in a way that it produces neither beauty nor desire; it usually forces the spectator to confront his or her own ‘animality’” thus being “a political statement in that both the subject and the spectator are debased, humiliated”, forcing “the spectator, especially the liberal intellectual, [to] question the real consequences of our idealism” (2015, 229). Reflecting on this aspect of his work, Martiel shares that his work is not about glorifying “the aesthetics of shock or gratuitous pain”, noting that “the elegance of visual language and the transmission of knowledge through art have always been vital to [him]”, where art can act as “an escape route, a refuge, a firearm, and a means to express [one’s self] freely” despite repression. He adds that this extends beyond borders, as the countries he had visited all held “a colonial past conditioning the present, where the same bodies are oppressed” like “victims of capitalism, colonialism, fascism, and racism” (Marsh 2025).

Finally, I address the work of Alcántara, which opens this paper. His work draws attention to a rise in dangerous infrastructure threatening the lives of Cubans both at home and in public. The tragedies which he was critiquing in Havana resonate with experiences in my field site of Santiago de Cuba, where collapsing balconies are signaled with caution tape and hand-painted signs. One of my research collaborators joked during a walk that it was not possible to walk while distracted, like using a phone, due to the danger. Often, signs were surrounded by small chunks of plaster and concrete, which signified the chance of a deadlier rupture. Collapses are worsened by the overcrowding and environmental context of Havana, provoking further concern. This is exemplified by Alcántara’s performance, which went viral, striking a nerve with concerned viewers, both for the repression of Cuba’s growing ‘artivism’ movement and for the likelihood of further casualties. Following the performance, he was arrested—one of over a dozen arrests across his career. A controversial artist, he rose up in alternative movements unofficially and is increasingly placed at the vanguard of dissent by critical foreign audiences and academics (Loss 2021). His work became increasingly political after Decree 349, a major legal precedent for the state’s control over artists through their work’s distribution, dissemination, and creation (Guerra 2021). The 2018 law targets independent creatives, who are described by state media as mediocre, vulgar, artistic intruders to protect hegemony (Loss 2021). His artwork and activism helped drive the J11 protest, the largest since the Revolution, in which he participated via a viral hunger strike, showing the role of media in challenging internal oppression. This earned him a place within Time Magazine's 100 most influential people of 2021; yet, as of the following year, he had served a five-year sentence, one of several creatives arrested for J11 (Font et al. 2024).

I urge readers to balance a desire for resistance in academic literature with concern over human lives. As Foucher (2024) argues, inspired by her friendship and collaboration with Alcántara, the media and academy’s desire for resistance can overshadow artistic media. I argue that a foreign posturing of artists as the face of dissent for a collapsing ‘totalitarian’ state is entangled with its sense of precarity and thus, violent responses. I urge caution unpacking critiques, as his work does not desire capitalism for Cuba, like coopted critical media (Farber 2023), but something new. In fact, he also criticized neoliberal market reforms and the state abandoning its values (Loss 2021; Foucher 2024). I argue that works engaging with ruin, memory, and criticality are polyphonic in nature. They highlight moments of rupture, repair, and collapse with lived implications on individual lives. They expose unspoken class-based anxieties of ruination; expositions that are not without risk.[22] I was forced to confront this as my main collaborator was removed from his role as museum director for displaying critical independent Cuban cinema, primarily for a film that engaged heavily with ruination as a sign of dystopia, as discussed by Juan-Navarro (2024). As Gordillo argues, rubble’s afterlife is “humanly mediated...people can, willingly or not, be socially predisposed to glorify, fear, or ignore the same ruin” (2014, 255). Romantic framings wither when met with fears of life amidst derrumbes, and power is drawn into the fray as the violence of ruins comes into focus. Creatives expose anxieties that otherwise remain buried, embodying the aesthetics of rubble, violence, and death to pursue better futures, despite increased odds of retribution.

L: Call for Help (2019); R: And What More? (2019). Photo credits: 2+2=5. Author’s translations.

Urban Art of Infrastructural Collapse: Symbolizing Rubble

Drawing from, and historically overlapping with, performance arts and street art in Cuba has always been materially entangled with political forces and urban space. The genre is valuable, despite being relatively understudied (excl. Cruikshank 2014; Dabène 2020; Hordinski 2020; Braziel 2022). In this section, I draw from social media profiles by Habanero street artists Yulier P and Fabian Lopez, known as “2+2=5”. Historically, and increasingly since the pandemic, Cuban street artists create directly on ruins and rubble to address infrastructural crises.[23] The genre is tied to precarity thematically and through material, economic, and political challenges. It is thus practiced by a comparative minority. Dabène (2020) argues that the Cuban state limits spray-paint imports, and like elsewhere, artists self-censor critiques to find fame. Most artists in Cuba, especially street artists, practice in Havana, but the art form does exist to lesser extents in other provinces. In my prior work, a participant witnessed police brutality in Santiago de Cuba against three teens for their street art; a mural he later photographed for my project (Smith 2024, 96).

L: The mural discussed above. R: Graffiti tag on an abandoned structure.[24]

With inconsistent risk in response to street art, symbolism is often necessary. Explicit activists often meet harsh responses, like El Sexto (see Fusco 2015), who now lives in the United States. Repression continues to grow for other creatives as difficulties amplify. Fabian Lopez, or 2+2=5, named after George Orwell’s 1984, uses masked figures to skirt controversy with political art by obscuring who he is questioning, but his title and content inherently point out the contradictions of state narratives. He has outwardly explained that his use of rubble helps avoid controversy; he paints a “facelift” on abandoned structures and rejects painting monuments (Dabène 2020, 191). His work deals with many topics within a central theme of deconstructing official narratives, an example of rubble used for rupture to draw attention to ongoing violence and repression, as argued by Gordillo (2014).

Still from a video, taken by the author, with three 2+2=5 tags visible.

In a serendipitous moment while writing the draft of this paper, I reviewed videos from a preliminary field visit to Havana in December 2022, prior to fieldwork the following summer. In the first video, from the window of a 1950s taxi, I recorded passing facades on Havana’s famous waterfront, El Malecón, a famous symbol for Cuba in art and culture (Simoni 2016; Herrera 2011; De Ferrari 2015). Alongside repaired buildings and locally inaccessible luxury hotels rest signs of collapse. Piles of rubble line the front of the first building. I am shocked by three visible tags by 2+2=5 I had not seen. The canvas choice addresses the fractured narrative of the slow death of a once beautiful edifice, lining an iconic road that is culturally significant for Cubans and tourists.[25] Havana’s famous sites are highly desired by street artists as impactful, visible sites, despite risks (Dabène 2020). With further serendipity, Yulier P., who had been documenting collapses on Instagram, shared a video of the building, where tags remain despite further decay on November 29th, 2024.[26]

Yulier’s recent work—and to some degree, Fabian’s—has become blunter since the J11 protests and the legal crackdown of artists with Decree 349, literally using rubble as a canvas to provoke foreign public attention. Prior to 2018, he denied that his work was resistance, but slowly grew critical, particularly as the police ordered him to impossibly erase all his paintings. Accused of “violation of social property”, he countered that, like 2+2=5, he only painted “abandoned buildings and ruins” (Dabène 2020, 193). In response, Alcántara hosted an exhibit ‘State Property Destruction’, to “change the image of graffiti writers", arguing “they were not dissidents in search of profound political change”, but instead producing transformative and beautifying work (ibid. 195). Similarly, both 2+2=5 and Yulier describe neighbours thanking them often for what Yulier calls “colorful paintings in their sad built environment” (ibid. 193).

L: Untitled (2020); R: Untitled (2019). Photo credit: Fabian Lopez.

Unlike Yulier, who risked retribution more openly, recent works by 2+2=5 are more symbolic, with critiques using veiled language in captions, with one calling for !Vive Cuba, pero libre! [long live Cuba, but freely; author’s translation]. His pieces include global critiques, with sensory disfigurement of masked figures commenting on themes like global finance. Conversely, Yulier P. has only grown more critical. One of his latest series placed painted bricks and rubble from derrumbes in visible, well-trafficked places in Havana, moving his signature alien-like figures from urban walls to their remains. They addressed issues of division, slogans, natural disasters, blackouts, infrastructure, protests, and political prisoners. They poignantly employed the materiality of decline, despite pushing boundaries by centering internal oppression. Pieces became increasingly confrontational alongside the crisis, leading to a boiling point.[27] He joins others experiencing the ‘social death’ of critical art (Fusco 2015), particularly after Decree 349, and, having recently emigrated, will face critiques like other diasporic artists.[28] In the pieces below, he discusses, respectively, the shared notion of Cubanidad, the controversial Patria y Vida [Homeland and Life], which reworks the state motto Homeland or Death, and Hurricane Oscar‘s ’abandoned’ victims.[29] The following triad addresses frequent blackouts since 2020, a bomb symbolizing the J11 protests unleashing pent-up pressure or frustration, and Cuban political prisoners, indexing a detour from symbolism against threats to artistic and personal liberties. However, to a lesser extent, he continues making works addressing global inequities, including the extensive loss of Palestinian lives and issues faced by migrants in Europe.

1: Shared Identity; 2: Lo Que Anda (What’s Going On); 3: The Abandoned;

4: Lo que nos UNE (what unites us)[30]; 5: 11th of July[31]; 6: 1000+ Political Prisoners.

Picture credit: Yulier P. (2024).

Resisting Ruins: Art(s) of Repair and the Search for New Rhythms

Moral Modulor (2012-2013), spliced slide film by Ernesto Oroza. From De Ferrari (2020).

By paying attention to the temporal rhythms and ruptures of the ruin, artists offer a counterpoint which can trouble foreign imaginaries and past framings of Cuban infrastructural decay. Occupying a range of perspectives and couched in varying degrees of symbolism and resistance, they remake ruins amidst material and societal constraints, calling idealism into question. Many of the works highlighted connect to a genre De Ferrari (2020) calls Cuban arts of repair, described as “a thoughtful praxis, based on a physical and conceptual engagement with materiality that seeks to make an imperfect world, and the lives embedded in it, as good as possible” (548). While agreeing, I emphasize her view that repair cannot overshadow structural violences requiring these solutions.[32] As I have highlighted, materiality cannot be extricated from Cuban visual media of precarity; it is literally shaped by material access, the political right to be labelled an artist (Guerra 2020; Loss 2021), and global connections (De Laforcade & Stein 2024), which artists thoughtfully engage with. These limits formed a class divide in Cuban art that limited critiques, one further changing with new technologies and growing urgency. Street art perhaps best exemplifies Cuba’s growing, but lagging, internet access to circumvent scarcity and censorship, reaching new audiences, with new dangers and rewards. It is critical to attend to both possibilities and constraints within these genres to help shape the futures they overlay onto our world.

I have sought to consider and trouble the generic imagery of the ruin, both through a foreign gaze historically, but also through academic attentions which often fail to note ongoing connections to new economic realities. Engaging with work by Gordillo (2014) and Suárez (2014), I connect these pieces to broader scholarly discussions of the dynamic nature of ruins, to address contemporary pieces using concepts of temporal rhythms and futurity, which have largely been used to reflect past periods in Cuba. I have attempted to balance my arguments and provide nuance to avoid contributing to processes of weaponization and Cuban exceptionalism. Audiences should exercise caution when engaging with ruination to not glamorize occupying ruined infrastructure as resistance, without foregrounding systematic violence. Without this caution, one may miss the necessary subtext to arguments, like from Park, that by making spaces to live within them, “it is possible to resist in ruins” (2012, 8) or from Sklowdowska that as “crumbling structures become reclaimed and creatively repurposed we are left with a glimmer of hope that human resilience might, in the end, transcend material ruination” (2021, 284). These quotes reflect the common tendency to conflate survival in Cuba with resistance, which has garnered more nuanced attention and apprehension in recent work (Garth 2020; De Ferrari 2020; Boudreault-Fournier 2023). I balance goals toward hopeful literature with my discomfort with uncritically using the term resistance. As Gordillo (2014) argues, it is political to allow things to become rubble. Thus, I argue that Cuban media of precarity foremost signifies violence despite being capable of troubling it—an intentional choice by many artists. I urge readers to ponder healthier futures outside preexisting molds, and to reflect on how Cuban creatives reject the conflation of criticism with adherence to foreign systems. Such works grow amid the rubble of a violent, unforgiving landscape that is never apolitical. They are not homogeneous; they exemplify or disrupt Camnitzer’s belief that Cuba is often the sole Latin American political art hoping to “refine the political structure rather than to destroy and replace it” (2009, 95). With growing critiques and urgency, concerns for human safety only increase.

Top: Reference photo of ruins;

Middle: First Sowing of Hallucinogenic Mushrooms in Havana (1997);

Bottom: Sea Water – Colosseum (2020).[33]

Embroiled by external and internal pressures and seeking purchase in precarity, Cuban media rejects expected futures, finding alternatives within the cracks of past dreams[34]. These pieces reflect arguments by Gandy (2022) and Tsing (2015) on urban ecologies, where unique relationships and rhythms emerge in the wake of human disasters. They echo that during precarity, "we don’t have choices other than looking for life in this ruin” (Tsing 2015, 6). Such approaches rebuild with the rubble of dying utopias, planting seeds from what works, and weeding out the rest. In doing so, they draw from political successes and failures, like pieces which critique the incongruities of both neoliberal and socialist discourses. I extend Price’s (2015) argument that Cuban media can reshape futures outside of prescribed rhythms. By remaking ruins and futures amidst them, we navigate the “imaginative challenge of living without those handrails, which once made us think we knew, collectively, where we were going” (Tsing 2015, 2). Thus, attuning to the rhythms and temporality of ruins as dynamic sites, through the lens of Cuban media of precarity, troubles static framings of ruins as “objects without afterlife” (Gordillo 2014: 9). Instead, rubble lingers in daily life, indexing many eras, fears, and hopes. I have aimed to show how engagement with the arts and research on the temporal rhythms of decay helps resuscitate narratives, peeling back layers of forgotten pasts and futures (see Boudreault-Fournier 2021), while consciously rejecting the seduction of ruins as profitable, commoditized sites that erase the lives within them.

Despite the foreign framings which shaped the growth of Cuban media of precarity, there may soon come a shift in foreign coverage. As violence becomes harder to exclude from the frame, ruins become harder to romanticize, shifting from indexes of nostalgia to something altogether new. As matter and time amble, the status of these structures moves across Gordillo’s hierarchy of materiality between rubble and ruin (2014, 10). At some point, peeling walls can decay too far, neglected by hostile politics and the violent tendrils of neoliberal capitalism. Faced with news coverage of crises and the counterpoint of new media, foreign audiences may snap out of an ideological, romantic reverie. As Cuban author Antonio José Ponte explains in the film Havana: The Art of Making Ruins, “inhabited ruins don’t allow a space for nostalgia”, with a “tragic possibility that one is ruining oneself inside of them” (in Park 2012, 4). While suffering subjects have historically imbued artwork of ruins with poignant, romantic meanings (Dillon 2006), this suffering, like infrastructural decay, can go too far. Breaking the reverie, contemporary artists reframe subjects under rubble, re-politicizing ruins. I conclude that one must exercise caution with simple narratives of resistance, but also decline, as critical literature threatens to do, particularly with recent media coverage of Cuban infrastructural decay, which only amplifies the foreign fascination with predicting Cuban futures. I remind readers of Tsing’s (2015) argument that, like progress narratives, preoccupations with decline can be equally damaging. Recalling the opening quote from Lezama Lima, the imagery of ruins can signify the death of cultures, and thus, the futures, once imagined, but also their resurrection in new forms. Their power ties to state fears of rubble as “an invitation to remake the world differently” (Gordillo 2014, 264). By highlighting lives within precarity, a dying romantic gaze is refracted to new audiences. As the visual-material traces of Cuba’s ruin memory are reimagined, something may start to rumble, perhaps with danger or possibility.

Endnotes

[1] “Media of precarity” can also be understood through Lauren Berlant’s work on cruel optimism, which addresses times in which the pursuit of desires may be harmful (such as the ‘American Dream’). While the work largely focuses on neoliberal capitalism, my analysis does take partial inspiration from their focus on media of precarity, which helps counter Cuban exceptionalism. They argue that the popularity of this media grew, largely since the 1990s, in response to common narratives of crises, as subaltern groups globally felt increasingly distant from “the good life” (2011: 7).

[2] While most scholars respond to romanticized framings in recent decades, instances extend throughout earlier eras (Gabara 2006; Schwartz 1997; Suárez 2014; Fraunhar 2019). Furthermore, Cuban author Desnoes (2006) wrote in the 1960s about how global perceptions of Cuban ruins in media shaped his own view of his country’s failings.

[3] Unruh describes how processes of innovation with both labour and materials are “key to survival, fending off collapse, or even generating hope” (2009, 200).

[4] While outside the scope of this paper, this can be valuably seen in the Cuban independent cinema genre, in films like Miguel Coyula’s Corazón Azul, which have been studied more recently than other genres using the theme of ruins (i.e. Juan-Navarro 2024; Sklodowska 2021).

[5] Demian has since been fired from this role, due to government disapproval of the range of media, including independent Cuban cinema, which he had displayed at the museum, which I discuss further elsewhere (Smith 2024). This led to his need to internally migrate to Havana, like many Santiagueros, to seek work and support his daughter.

[6] The challenge of romanticizing contemporary ruins is noted by scholars, such as Dillon (2006).

[7] There has been a historical preoccupation with predicting or anticipating specific futures for Cuba, particularly in terms of the collapse of an ‘authoritarian’ regime or transition towards other political economies, particularly neoliberal capitalism. I apply the term post-Soviet for Cuba to reflect the clear rupture which occurred after the collapse of the USSR, rejecting post-socialism as a label which does not accurately reflect the Cuban context.

[8] I direct readers to further explore other pieces which incorporate these themes valuably, but which are outside of the paper’s scope: Alfredo Sarabia Jr., Raul Cañibano, Ernesto Oroza (see De Ferrari 2020), and Grethell Rasúa (see Fusco 2015).

[9] These pieces belong to a long-time series showing the afterlives of buildings by photographing them prior to demolition, representing their ongoing memory and juxtaposing their afterlives, or ghosts. The goal is to encourage viewers to ponder ideology, memory, and temporality, combining both processes of destruction and creation.

[1o] Dopico rightfully argued that at this time, the framing of “the romantic ruins of a picturesquely suspended Havana... [was] not merely an aesthetic rediscovery or the latest fashionable migration of the image market”. Instead, it held “a banal and ominous significance for a city that lives in multiple temporalities...negotiating survival and ideology”, often through improvisation (2002, 451).

[11] Reclaiming visual iconography of the tourist gaze is common in Cuban arts, including Esterio Segura’s reclaiming of the 1950s Chevrolet and similar vehicles, a semiotic index of a temporally frozen Cuba (Sheller & Urry 2004: 3; Simoni 2018), into a symbol of futurity, mobility, and constraint of global and internal hostility. Several of these pieces are on display internationally, including in Tampa, Florida, where I was able to witness his 2016 piece ’Hybrid of a Chrysler’. (The vehicle now overlooks a view of the city from the museum’s balcony).

[12] I direct the reader to the work of Sklowdowska (2021), who is perhaps the most important contemporary writer reflecting on Cuban media of precarity and ruination, furthering these notions of utopia, dystopia, and modernity, often through the lens of abandoned sugar plantations.

[13] Profits went to only a select few local artists, while foreign photo-book sales grew. In one photo-book about Cuba, the author Jenkins tellingly describes Cuba as a place where “everything is transformed into an icon” (2002, 26).

[14] While the process abounds in tourist media, romanticized ruins are losing academic focus, excluding Ogden (2021)’s work on Instagram filters for tourists.

[15] Interestingly, this is not the sole tie between visual anthropology and Cuban performance art. Abdel Hernández, influential in 1980s Cuban art, collaborated with anthropologists of the Writing Culture movement who inspired his work. He produced a piece in 1989 called “ST”, involving the theme of burial and rubble. However, beyond a visual image, there is no contextual information, like other pieces of the era. He later co-founded the Transart Foundation for Art and Anthropology.

[16] De Ferrari (2020) notes an ironic instance of urban infrastructural repair where a state project was simulated to drown out dissent. Tania Bruguera, orating Arendt’s The Origins of Totalitarianism during house arrest to passerby, was met by officials’ stating, despite having recently repairing her road, that a mistake was made, requiring the din of jackhammers to drown out her opposition.

[17] The work could also be seen as an example of “visual biopolitics”, which Tobing-Rony (2022) argues includes the possibility for rupture through media, which can challenge processes like necropolitics where human bodies become the evidence of political violence.

[18] Elsewhere, cemeteries have been discussed as sites of decay and inequality for Cubans (Cruz 2022), as artistic agencies responded to power and unequal burials.

[19] Initial examples commented on control while he was solely living in Cuba to reflect on infrastructural collapses and environmental racism, with increased precarity for Afro-Cubans despite state discourses of equality. More recent work reflects his life in the diaspora, working between Havana and, primarily, New York City.

[20] See opening photo to this section.

[21] Other works include other forms of transgression, often involving self-inflicted or condoned violence and pain to confront viewers with this legacy, like subjecting himself to fumigation in Havana to comment on gusanos [worms/traitors], creating a medal through surgery from his flesh, piercing an American Flag through his shoulder, and subjecting himself to the ocean’s force through burial and chains on Havana’s shores.

[22] Gordillo (2014) argues that these anxieties are erased by power globally, something which Gandy extends to class, gender, and racialization (2022, 113).

[23] Historical precedents include the afore-mentioned ArteCalle, who used graffiti alongside performances, and Robert Diago’s provocations about Cuban racism driven by globalization (Fernandes 2006).

[24] This photo was taken on one of three shared 35mm film cameras which were used jointly on photo-walks; thus, I am unsure of the exact author or intention behind the photo. Nonetheless, it is an example of graffiti tags by locals on decaying infrastructure. On photo-walks where we saw the piece on the left, triggering its associated memory for the participant, we also saw several pieces by foreign graffiti artists. While outside the scope of this piece, they included interesting elements, such as a piece from a Dutch artist depicting Frankenstein’s monster asking, “wait, is this illegal?”.

[25] Further examples, including on migration, fall outside of this paper’s scope, but can be found on the 2+2=5 Instagram page.

[26] The video can be found at: https://www.instagram.com/p/DC9GMeyRgW2/.

[27] Since drafting this paper, he has recently fled to Madrid and is posting new work on migration, like much of the Cuban artistic diaspora, many of whom seek out Spain’s art scene.

[28] Still, he has in the past self-identified more as an artist than a dissident, noting the latter, like El Sexto, were “at war with Fidel Castro”, while his “dialogue with the public through art” employed “some lyricism” (in Dabène 2020, 194).

[29] Another of the tropical storms that the island struggles to weather, which amplifies issues of infrastructural decline.

[30] The title is a clever pun on the Cuban Electric Union, which uses the acronym U.N.E., reflecting increasing blackouts and failing infrastructure tied to notions of ruination. During my fieldwork, almost daily blackouts would last up to four hours, but had been much higher the year before, and in the time since. It is also notable that the final piece is placed quite visibly on Havana’s famed sea wall for tourists and locals to absorb.

[31] Yulier has begun to use this photo printed on stickers as a street art piece in Madrid, since emigrating in 2025.

[32] At times, creative methods and repair cease to be enough in the face of growing structural violences, particularly as artists’ impacts are minimized in recent years. There is arguably a tendency in Cuban studies to overemphasize survival strategies, to show resilience, and with increasing pressures, strategies for repair are evolving, and may require larger changes beyond the everyday resolution of shortages, which continues to become more difficult.

[33] This work juxtaposes his actual photo of a building in ruination with an architectural sketch discussing ideas of hallucination, implying the idea of imaginaries and temporality within utopian visions.

[34] This theme is one of the most notable across Cuban media forms, deserving further attention in relation to other genres. It is also common in independent cinema (Sklowdowska 2021; Juan-Navarro 2024), Cuban literature (De Ferrari 2007; Oliveira 2013; Suárez 2014; Price 2015; Loss 2021), collage pieces by Castañeda (Craven 1992), other paintings by Humberto Calzada (Bosch 2008), and multimedia pieces by Sandra Ramos.

Acknowledgements

Dedicated to my partner Jessica, to the Cuban creatives without whom my work would hold very little meaning, and to those working toward a better future on the horizon amid violent and draining times.

References

Bosch, Lynette M. F. 2008. “Humberto Calzada,” pp. 20-29 in Identity, Memory, and Diaspora: Voices of Cuban-American Artists, Writers, and Philosophers, eds. Gracia, Bosch, & Borland. 2008. New York: SUNY Press.

Boudreault-Fournier, Alexandrine. 2021. “Intimating the Possible Collapse of the Future: Digging into Cuban Palimpsests Through Innovative Methodologies,” pp. 227-253 in In Search of Lost Futures, Anthropological Explorations in Multimodality, Deep Interdisciplinarity, and Autoethnography. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

———. 2023. “Under Pressure: Catching the Pulse of a Cuban Crisis.” EPD: Society and Space 41(3): 392-410.

Braziel, Jana Evans. 2022. Street Art and Activism in the Greater Caribbean: Impossible States, Virtual Publics. New York: Routledge.

Buschschlüter, Vanessa. 2023. “Building collapse in Havana's old town kills three.” BBC News, Retrieved October 5, 2025 from https://www.bbc.com/news/world-latin-america-67016781.

Camnitzer, Luis. 2009. On Art, Artists, Latin America, and Other Utopias. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Cepero, Iliana. 2019. “Cuban Photography after 1959: Shifting Paradigms,” pp. 144-154 in Picturing Cuba: Art, Culture, and Identity on the Island and in the Diaspora. Ed. J. Duany. Gainesville: University of Florida Press.

CiberCuba. 2024. “Week of collapses in Cuba: A foretold tragedy.” CiberCuba Noticias, June 22, 2024. Retrieved October 2 from https://en.cibercuba.com/noticias/2024-06-22-u1-e199370-s27061-nid284000-semana-derrumbes-cuba-tragedia-anunciada.

———. 2025. “One person dies due to a collapse in Old Havana.” CiberCuba Noticias, September 28, 2025. Retrieved 10/02/2025 from https://en.cibercuba.com/noticias/2025-09-28-u1-e208512-s27061-nid311888-muere-persona-derrumbe-habana-vieja.

Craven, David. 1992. "The visual arts since the Cuban revolution." Third Text 6: 77-102.

Cruikshank, Stephen. 2014. “Concrete Impressions: A Poetic Vision of Cuban Graffiti.” TranscUlturAl 6(1): 11-15

Cruz, Lynn. 2022. Crónica Azul. Prague: Editions Fra.

Dabène, Olivier. 2020. “Havana: Going Public, No Matter What,” pp. 183-216 in Street Art and Democracy in Latin America. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

De Ferrari, Guillermina. 2007. "Cuba: A Curated Culture." Journal of Latin American Cultural Studies 16(2): 219-247.

———. 2015. Apertura: Photography in Cuba Today. Madison: University of Wisconsin Chazen Museum of Art.

———. 2020. “Net, Module, Chance: Repairing Cuba.” International Journal of Postcolonial Studies. 23(4): 544-569.

De Laforcade, Geoffroy & Daniel Stein. 2024. “Beyond Scarcity and Hardship: Historical and Contemporary Reflections on Cuban Comics.” Forum for Inter-American Research 17(1): 22-39.

Desnöes, Edmundo. 2006 [1st ed. 1988]. “The Photographic Image of Underdevelopment,” trans. J. Lesage. Jump Cut 33: 69-81.

Dillon, Brian. 2006. “Fragments From a History of Ruin: Picking through the wreckage.” Cabinet Magazine 20(1).

Dopico, Ana Maria. 2002. “Picturing Havana: History, Vision, and the Scramble for Cuba.” Nepantla: Views from South 3(3): 451-493.

Duany, Jorge. 2019. Picturing Cuba: Art, Culture, and Identity on the Island and in the Diaspora. Gainesville: University Press of Florida.

Eaton, Tracey & Katherine Lewin. 2018. “How Havana is collapsing, building by building.” USA Today, December 2, 2018. Retrieved October 2, 2025, from https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/world/2018/12/02/havana-cuba-collapsing-buildings-housing-unesco/1998606002/.

Font, Solveig, Coco Fusco, Celia Irina González, Hamlet Lavastida, Julio Llópiz Casal, & Yanelys Nuñez Leyva. 2024. “Can a Biennial Respect Difference in a Country that Represses Dissidence?” e-flux, September 13, 2024. Retrieved September 9, 2025 from https://www.e-flux.com/notes/627502/can-a-biennial-respect-difference-in-a-country-that-represses-dissidence-on-the-havana-biennial.

Fernandes, Sujatha. 2006. Cuba Represent!: Cuban Arts, State Power, and the Making of New Revolutionary Cultures. Durham: Duke University Press.

———. 2020. The Cuban Hustle: Culture, Politics, Everyday Life. Durham: Duke University Press.

Foucher, Joséphine. 2024. Revelations of the aesthetic experience: artistic creation under constraint in contemporary Cuba. PhD Dissertation. The University of Edinburgh.

Fraunhar, Alison. 2019. “Colonial Art and Its Afterlife: Visualizing the Nation Then and Now,” pp. 51-69 in Picturing Cuba: Art, Culture, and Identity on the Island and in the Diaspora, ed. Duany. Gainesville: University of Florida Press.

Fusco, Coco. 2015. Dangerous Moves: Performance and Politics in Cuba. London: Tate Publishing.

Gabara, Esther. 2006. ““Cannon and Camera”: Photography and Colonialism in the Américas.” English Language Notes: Photography and Literature 44(2): 45–64.

Gandy, Matthew. 2022. Natura Urbana: Ecological Constellations in Urban Space. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Garth, Hanna. 2020. Food in Cuba: The Pursuit of a Decent Meal. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Gordillo, Gastón. 2014. Rubble: The Afterlife of Destruction. Durham: Duke University Press.

González Álvarez, Celia. 2022. “Tarde de Sándwiches: the failure of participation in contemporary Cuban art,” in The Failures of Public Art and Participation, eds. C. Cartiere & A. Schrag. London: Routledge.

Guerra, Lillian. 2021. “Decree 349 and Today’s History of Artistic Expression in the Cuban Revolution: A Review Article.” Cuban Studies 50: 333-345.

Herrera, Andrea O’Reilly. 2011. Cuban Artists Across the Diaspora: Setting the Tent Against the House. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Hordinski, Madeleine Z. 2020. “Public and Private Spaces for Art and Dissent in Post-Fidel Cuba.” The Macksey Journal of National Undergraduate Research 1(Article 118).

Jenkins, Gareth. 2002. Havana in my Heart: 75 Years of Cuban Photography. Chicago: Chicago Review Press.

Juan-Navarro, Santiago. 2024. “Fading Utopias: The Critical Unveiling of Revolutionary Ideals in Cuban Speculative Cinema.” Recent Research Advances in Arts and Social Studies 7(6): 156-179.

Kovach, Jodi. 2016. “Architectural Ruins and Urban Imaginaries: Carlos Garaicoa’s Images of Havana.” Contemporaneity: Historical Presence in Visual Culture 5(1): 72-84.

Lezama Lima, José. 1972. "Imagen de Americá Latina," pp. 462-8 in América Latina en su Literatura, ed. C. Fernández Moreno. México City: Siglo XXI Editores; Paris: UNESCO.

Loss, Jacqueline. 2021. “Socialism with Bling: Aspiration, Decency, and Exclusivity in Contemporary Cuba.” Journal of Latin American Cultural Studies, 30(2): 291-310.

Manuel Álvarez, Carlos. 2020. “Cuba arrested a performance artist because he’s everything the regime can’t control.” Washington Post, March 11, 2020. Retrieved September 9, 2025 from https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2020/03/11/cuba-arrested-performance-artist-because-hes-everything-regime-cant-control/.

Martí Noticias. 2020. “Detienen al artista Luis Manuel Otero Alcántara por performance contra derrumbes.” Retrieved December 15, 2024 from https://www.martinoticias.com/a/detienen-al-artista-luis-manuel-otero-alc%C3%A1ntara-por-performance-contra-derrumbes/257632.html.

Marsh, Walter. 2025. “He’s been hanged, stabbed and cut in galleries – now artist Carlos Martiel is being buried alive.” The Guardian. Retrieved November 7, 2025 from https://www.theguardian.com/culture/2025/jun/05/carlos-martiel-artist-dark-mofo-festival-hobart-tasmania-buried-alive.

Memory of Nations. 2020. “Luis Manuel Otero Alcántara.” Retrieved September 5, 2025, from https://www.memoryofnations.eu/en/otero-alcantara-luis-manuel-1987.

Moya, Natalia L. 2025. “Two Havana Building Collapses with Four Deaths.” Havana Times, July 13, 2025. Retrieved October 2, 2025 from https://havanatimes.org/news/two-havana-building-collapses-with-four-deaths/.

Normand, Adriana. 2023. “Sad Waltz between Collapsing Buildings & Poverty in Havana.” Havana Times, October 11, 2024. Retrieved October 2, 2025, from https://havanatimes.org/opinion/sad-waltz-between-collapsing-buildings-poverty-in-havana/.

Otix, Jordi., Manu Mitru, Laura Luque, & David Melero. 2023. “The Cuban Collapse – a photo essay.” The Guardian, March 13, 2023. Retrieved December 20, 2024, from https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2023/mar/13/the-cuban-collapse-photo-essay.

Park, Paula C. 2012. “Living Dangerously: Florian Borchmeyer’s Havana: The New Art of Making Ruins (2007).” Sin Frontera: Revista Académica y Literaria 6.

Powell, Kathy. 2008. “Neoliberalism, the Special Period and Solidarity in Cuba.” Critique of Anthropology 28(2), 177-197.

Price, Rachel. 2015. Planet/Cuba: Art, Culture, and the Future of the Island. London and New York: Verso Books.

Quiroga, José. 2005. Cuban Palimpsests. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Roland, L. Kaifa. 2010. Cuban Color in Tourism and La Lucha: An Ethnography of Racial Meanings. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Schwartz, Rosalie. 1997. Pleasure Island: Tourism and Temptation in Cuba. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

Sheller, Mimi & John Urry. 2004. Tourism Mobilities: Places to Play, Places in Play. London and New York: Routledge.

Simoni, Valerio. 2016. Tourism and Informal Encounters in Cuba. New York: Bergahn.

———. 2018. “Approaching Difference, Inequality, and Intimacy in Tourism: A View from Cuba.” Journal of Anthropological Research 74(4).

Sklodowska, Elzbieta. 2021. “All That is Solid Melts Into Rust: The Material Decay of The Sugar Industry in Post-Soviet Cuba.” Journal of Latin American Cultural Studies. 30(2): 277-290.

Smith, Graydon. 2024. Reframing Crisis: Hope and Future-Making in Contemporary Cuban Photographs. MA Thesis. University of Victoria. https://hdl.handle.net/1828/20393.

———. Forthcoming. No Hay un Futuro Aquí: Re-framing Cuban Futures and Migration in Crisis.

Stoler, Ann L. 2013. Imperial Debris: Reflections on Ruins and Ruination. Durham: Duke University Press.

Suárez 2014. “Ruin Memory: Havana Beyond the Revolution.” Canadian Journal of Latin American and Caribbean Studies 39(1): 38-55.

Thompson, Krista. 2007. An Eye for the Tropics: Tourism, Photography, and Framing the Caribbean Picturesque. Durham: Duke University Press.

Tobing Rony, Fatimah. 2022. How Do We Look?: Resisting Visual Biopolitics. Durham: Duke University Press.

Tsing, Anna Lowenhaupt. 2015. The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Unruh, Vicky. 2009. “All in a Day’s Work: Ruins Dwellers in Havana,” pp. 197-209 in Telling Ruins in Latin America, eds. Unruh & Lazzara. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

14yMedio. 2024. “A 60-Year-Old Man Dies in the Collapse of a Building in Guanabacoa, Cuba.” Translating Cuba, November 3, 2024. Retrieved October 2, 2025, from https://translatingcuba.com/a-60-year-old-man-dies-in-the-collapse-of-a-building-in-guanabacoa-cuba/.

———. 2025a. “An Elderly Man Dies in a Building Collapse in Old Havana.” Translating Cuba. September 9, 2025. Retrieved October 2, 2025, from https://translatingcuba.com/an-elderly-man-dies-in-a-building-collapse-in-old-havana/.

———. 2025b. “Café Worker Dies in Building Collapse in Central Havana.” Havana Times, August 14, 2025. Retrieved October 2, 2025 from https://havanatimes.org/news/cafe-worker-dies-in-building-collapse-in-central-havana/.