Poetic Resistance: Examining the Conceptual Relationship Between Weaving and Poetry as an Embodied Form of Resistance in the Work of Cecilia Vicuña

Eva Lynch

Department of Anthropology, McGill University, Canada

Abstract This paper explores Chilean artist Cecilia Vicuña’s 1997 collection QUIPOem/The Precarious: The Art and Poetry of Cecilia Vicuña, examining her approach in poetry and visual art, particularly through her reclamation of the ancient Andean practice of quipu weaving, as a means of resistance against colonial erasure. QUIPOem, and Vicuña’s work at large, is a meditation on language, loss, and reclamation, where Vicuña uses the relationship between poetry and weaving as a metaphor for language and memory to create thought-provoking pieces which are an expression of resistance and a tool to critique the politics in post-dictatorship Chile. Vicuña’s installations both aim to resurrect the lost woven language of her Indigenous ancestors while simultaneously highlighting how this language is irrecoverable as its historic meanings have been erased and obfuscated by colonial powers. Her work interrogates the possibilities of embodied forms of poetic resistance and explores how this defiance can materialize through her own reflections on the past as it intertwines personal and political narratives, and she thinks about environmental destruction and institutional forms of violence, considering the impact of colonization and dictatorship on cultural memory in Chile.

Résumé Cet article explore la collection de 1997 de Cecelia Vicuña, QUIPOem/The Precarious: The Art and Poetry of Cecilia Vicuña, et examine son approche poétique et pratique dans les arts visuels, notamment à travers sa récupération de l’ancienne pratique andine du tissage du quipu, comme moyen de résistance à l’effacement colonial. QUIPOem est une méditation sur le langage, la perte et la récupération, les thématiques typiques de Vicuña. Elle s'intéresse à la relation entre la poésie et le tissage comme métaphore du langage et de la mémoire. Elle s’appuie sur cette métaphore pour créer des œuvres qui sont à la fois une expression de résistance et un outil pour critiquer la politique post-dictatoriale au Chili. Ses installations visent à ressusciter la langue tissée perdue de ses ancêtres indigènes, soulignant le fait que cette langue est irrécupérable puisque ses significations historiques ont été effacées et obscurcies par les puissances coloniales. Son travail questionne les possibilités de formes de résistance poétiques et explore comment ce défi peut se matérialiser. Ses œuvres entremêlent expériences personnelles et politiques, en abordant la destruction de l'environnement et la violence institutionnelle, tout en considérant l'impact de la colonisation et de la dictature sur la mémoire culturelle du Chili.

Keywords Weaving, Poetry, Resistance, Colonialism, Cecilia Vicuña, Quipu

Introduction

In 1973, Chile’s democratically elected president, Salvador Allende, was overthrown in a coup d’état led by General Augusto Pinochet, ushering in a military dictatorship which reshaped the nation’s social and cultural fabric for decades to come. The dictatorship, which lasted until 1990, marked one of the most brutal periods in Chile’s history, deepening social inequality as thousands of Chileans were imprisoned, tortured, and disappeared, while many artists, writers, and intellectuals were forced into exile. During this violent rupture, Chilean poet and experimental artist Cecilia Vicuña, who was studying in London and forced into self-exile, emerged as one of Chile’s most radical voices and dissidents. Revered for her cryptic forms of resistance to Pinochet’s regime, her multidisciplinary practice—encompassing poetry, weaving, performance, and installation art—draws on Indigenous Andean traditions to interrogate the intertwined legacies of colonialism, patriarchy, and state violence (Lynd 2005, 1588). Vicuña's work has been recognized for its themes of language, memory, dissolution, extinction and exile, acting as a counternarrative to the history of colonization and the loss of Indigenous cultures which the dictatorship exacerbated. She critiques Chile’s politics of memory and reconciliation, questioning the state’s persistent silence as it continues to bury its past, rather than make reparations for its wrongs (Díaz 2018, 181). Through her work, Vicuña mobilizes Indigenous practices not merely to represent resistance, but to perform it into being, transforming ancient forms of knowledge, such as quipus, into contemporary tools of political and poetic dissent.

This paper aims to analyze how Cecilia Vicuña’s weaving and poetry function as embodied forms of resistance, situating her practice within both Chile’s post-dictatorship politics and broader Indigenous epistemologies. My analytical approach draws on theories of materiality, decolonial aesthetics, and Indigenous temporality to show how weaving operates not only as a metaphor but as a political practice. Investigating weaving as an epistemological method highlights Vicuña’s woven practice as both a testament to the endurance of Indigenous thought as well as a generative site for agency and the creation of alternative social imaginaries, by reconceptualizing weaving as a living practice of decolonial resistance. Her work expresses an ecological and political vision where nature, culture, and community are entwined, to offer an alternative to the destructive forces of capitalism and colonialism. In reclaiming Indigenous artforms and epistemologies such as the quipu—an ancient Andean system of knotted cords—as both a material practice and metaphor, I argue that Vicuña enacts a poetics of resistance which sustains an ongoing dialogue between past and present, between what has been lost and what can still be reimagined, as she works towards a decolonial and feminist future.

Vicuña began making her own versions of quipus in the 1960s as a part of her practice. Quipus, an ancient Andean system of knotted cords, existed for thousands of years as a vital medium of measuring, recording, and communicating among the Quechua people, before being banned and burned by Spanish colonizers in the sixteenth century. Argentine semiotician Walter Mignolo explains that quipus, along with other nonalphabetic forms of ‘writing’ such as Mesoamerican hieroglyphs, were devalued by sixteenth-century Europeans in favor of an alphabetic text, which quickly established its authority through expanding colonial efforts (Lynd 2005, 1591). Europeans’ inability to read or understand quipus resulted in their recognition as a threat to settler-colonial power. By returning to this practice of quipu making and knotting, Vicuña seeks to reactivate the spirit of ancient Latin American cultures touched by colonialism and embraces more traditional methods of narrating histories which have been historically silenced and overlooked. She sees the quipu as a visual poem in space, a metaphor and way of both remembering and reclaiming the past (Crain 2020). Deterritorializing colonial concepts which have perpetuated language, art and meaning-making in her reclamation of pre-Columbian practices, Vicuña uses metaphor as a poetic tool to connect dissimilar entities. She revisits not only her personal past but the broader colonial past in Chile to rethink revolutionary ideas which remain vital to contemporary challenges in a society structured by rigid binaries and social hierarchies inherited from colonialism (Lynd 2005, 1590). Through quipus, she reflects on the erasure of her own Indigenous history and lineage, and her mother and grandmother’s suppression of their Indigenous identities (Crain 2020). Vicuña’s reclamation of these ‘lost’ techniques pays homage to the loss of Indigenous cultural practices, languages and lives at the hands of the colonial project across Latin America, transforming remembrance into an act of creative resurgence.

Her textile installations are symbolic of the attempted colonial erasure of language and practices, and prompt renewed discourse around the histories of Indigenous cultural resistance and perseverance in the face of colonization. For Vicuña, reviving quipus becomes a way of thinking through loss while simultaneously reactivating what colonial and state violence sought to erase. She highlights weaving as a tool of opposition and symbol of resilience through its persistence as an adapted form of traditional practice and method of storytelling, in spite of the fact that there are unrecoverable elements of the practice which have been forever forsaken and destroyed by colonialism. Resilience, in this context, refers not simply to endurance but to the capacity to generate new possibilities for collective memory and cultural critique.

This paper focuses on her 1997 collection of work: QUIPOem/The Precarious: The Art and Poetry of Cecilia Vicuña. In QUIPOem, the act of knotting is inseparable from the act of remembering. The book is a thirty-year retrospective of Vicuna's poetry, visual and narrative responses to Chile’s historical struggle with dictatorship and democracy (Lynd 2005, 1590). QUIPOem showcases her poetry and photography alongside an interview and four critical essays by scholars Lucy R. Lippard, Catherine de Zegher, Hugo Mendez-Ramirez and Kenneth Sherwood[1]. This essay examines how Vicuña weaves together poetry and textile practice as a tool of resistance against colonial erasure. At its core lies a set of intertwined questions about reconciliation, reclamation, and meaning: how can a lost language be resurrected while acknowledging that its original meanings can never be fully recovered? The tension between Vicuña’s desire to restore meaning and the impossibility of doing so lies at the heart of her poetic resistance. She turns to the very processes through which meaning is constructed to ask: when a language has been emptied by colonial violence, what can be reclaimed through embodied, material engagement with Indigenous cultural practices and aesthetics as acts of dissent?

Textile Textualities: Language, Weaving, and the Poetics of Resistance

If Vicuña’s conception of weaving acts as a form of political resistance to colonial erasure, its translation into her poetry investigates the very mechanisms through which meaning is made and unmade. Her poetics of resistance are inseparable from the linguistic structures and poetic devices through which language is composed and serve as a way to interrogate the colonial logics embedded in language itself. The threads of her poems—linguistic, material, and conceptual—expose how words can both carry and conceal power. In this sense, her investigation of the relationship between weaving and poetry is not merely formal but epistemological, asking how language might be used to articulate what colonial violence has rendered unspeakable.

Vicuña initially began investigating the etymological connection between weaving and language to see how language mirrors the structure and logic of weaving. By tracing the roots of the words text, textile, and textuality to the Latin term textere—meaning ‘to weave’ in reference to the way words and sentences are “woven” together—she examines how meaning is made and ‘woven’ into existence; how we speak of “weaving” a tale or “spinning a yarn.” In Quechua, this connection is deepened, as the word for language is synonymous with "thread" and the term “embroidering” refers to complex conversation (Lippard 1997, 11). Across both traditions, the parallel between weaving and poetry emerges not only metaphorically but structurally, through rhythm, repetition, and meter, as well as the act of threading together ideas and yarn to bring form into being (Howard 2002).

This etymological approach frees words from the rigid expectations of language to more loosely construct our own varied lived experiences. Poet and professor José Felipe Alvergue suggests that in the context of Vicuña’s work, poetry “imparts meaning from within the gaps and fissures of time, giving form to the ‘open’ spaces and abstract arrangements available for engaging in shared politics” (2014, 91) and offers the artist the possibility of finding their own gestures ascribed with new meaning. Thus, in her work, Vicuña plays with the weaving and unweaving, or making and unmaking, of meaning; as she reclaims a practice whose language she may never fully understand, but whose epistemology she embraces. Vicuña reconsiders the changes of the signified into the signifying and vice versa, as she “dwells in im/possibility” (de Zegher 1997, 41). Her poetry demands that these mechanisms be laid open to investigate how we produce meaning, particularly examining the formation of a language, as she looks to weaving as a visual form of language, which “speaks of its own process: to name something which cannot be named" (ibid.).

Vicuña takes a deconstructivist approach to her poetry by embracing Indigenous ontologies and conceptualizations of the world during her investigation into the formation of language and its relationship to weaving and other visual forms of expression. For Vicuña, “the poem is not just an object that can be found or lost; it can also be a spirit, experience, or protest exuded by the poet. The written word on the page is only the smallest remnant of the poem, which is really the life, or shared life, of its poet” (Soto 2019). The poem is both an extension of Vicuña and her inquiry, while simultaneously agential and operating of its own accord when given life through Indigenous ontologies, where the poem takes on its own lifeforce as it is the enduring spirit of the poet. From this perspective, even if tools for understanding a poem have been lost, the poem continues to live on since its spirit can never be lost. This framing articulates how her poetry challenges our contemporary thoughts on the formulation and mechanisms of language, which continue to perpetuate the idea that what has been lost to colonialism can never be faithfully recovered.

Through this approach, Vicuña’s understanding of the poem as a living, agential force translates directly into her weaving practice, where language, materiality, and gendered labor converge as intertwined sites of resistance. In articulating the parallels between the crafting of poetry and the semiotics of weaving, Vicuña’s textile-textual practice underscores the unspoken and unwritten stories of women and Indigenous communities, from whom these weaving techniques originate (Lynd 2005, 1590). Vicuña’s approach departs from prior feminist scholars, like Susan Gubar, who have studied weaving as a devalued form of textuality to language, by instead interpreting it as a blank page which contains the untold stories of women[2] (Gubar 1981). In reclaiming these weaving practices and by threading this poetic metaphor throughout all of her work, Vicuña’s decolonial approach foregrounds the experiences of women and other underrepresented individuals who have been silenced through the loss of their language and erasure of their traditions. By drawing a parallel between weaving and writing, Vicuña carves out an alternative possible world and attempts to counter the consequences of state violence and disruption of traditional practices, such as the destruction of quipus, where poems, stories and worldviews were once contained.

Vicuña’s appeal to the etymological origins of textuality in women's textile arts evokes discourse around the historic and contemporary plight of weavers who have been silenced by the cultural legacies of colonialism (Lynd 2005, 1605). Vicuña’s engagement with weaving highlights the strength of material cultural practices and their resistance to forces of modernization. Through analyzing her work, it becomes clear how her work reframes weaving practices as a poetic and embodied form of resistance as they have persisted against both colonialism and modernization (Lynd 2005, 1590). Furthermore, the etymological technique Vicuña uses often flips hegemonic concepts on their head to reclaim the power of linguistic tools which have played a role in the erasure or suppression of voices. To do so, she examines the overlooked stories and meanings embedded in these art forms, which only come to light when she begins to deconstruct the practice for herself.

This notion is exemplified in her PALABRARmas. Engaging similar word play to QUIPOem, her PALABRARmasare a series of illustrations that aim to mobilize poetic language as a form of political resistance, through playful drawings of the reinvented meanings of existing words or their etymological double-meanings (Museum Label for Cecilia Vicuña, MoMA). The name itself is a neologism, which translates to “word-weapons,” enabling Vicuña to focus on words and their many poetic meanings instead of as only a component of threads or metaphors. In her accompanying poem to the illustrations, she concluded that the “individual words opened to reveal their inner associations, allowing ancient and newborn metaphors to come to light” (Vicuña 1984, 63), and thus posits that to approach words from a poetic approach is a form of asking questions. For Vicuña, poetry and weaving are continuous gestures—acts of creation and remembrance through which the ephemeral becomes political.

Vicuna suggests that once we breach the surface of words and enter their etymologies, we can see how the languages and cosmogonies of many cultures are intertwined—yet the memory of this connection disappears when a language loses its capacity to communicate this core value. As Latin American poetry professor Hugo Méndez-Ramîrez articulates in his companion essay to QUIPOem, “when the correspondence and cohesion between the name and that which is named is broken” (1997, 66), emphasizing the magnitude of the rupture caused by colonialism which persists today. In carving out a space for asking questions and having open dialogue by making weaving a form of political participation, Vicuña affirms her perspective of weaving as an "alternative discourse and a dynamic mode of resistance" (de Zegher 1997, 27). Aligning herself with a tradition of Indigenous Latin American feminist thought, we see how she uses weaving to disrupt official, authoritative discourse by creating unconventional modes of communication which question the legitimacy of existing power structures.

Materiality and Memory: Studying Precarios and Quipus

Where Vicuña’s poetry interrogates language as a site of resistance, her material practice grounds those same questions in the physical world. Through touch, texture, and the transformation of found materials, she applies her decolonial and feminist inquiry to her material practices. This shift is exemplified in QUIPOem, along with other sculptural projects, where resistance occurs through the act of making. In its efforts to counter the silencing effects of colonial and patriarchal power, QUIPOem foregrounds two interrelated concepts central to her practice: precarios and quipus. Together, these themes embody her commitment to subverting political hegemony and reclaiming her past through tactile engagement. First produced during her self-exile from Chile following the violent CIA-supported and Pinochet-led military coup in the early 1970s, her arte precario, or precarios, materialize life’s fragility and resilience. They are embodiments of life's precariousness, leaning into ephemerality, impermanence, and anti-monumentality as a mode of political and aesthetic resistance (Jorquera 2017). Vicuña crafts sculptures from debris and found objects, which she photographs and then leaves to the forces of time. Her precarios are made to engage and embody ‘maximum fragility’ as a means to challenge ‘maximum power’ (Vicuña 1983, 41); they use the past in order to see the present, building on the premise that the present is defined by how we see our past, how we treat it, how we ignore it or attend to it (Osman 2007, 123). She encourages people to be critical of the world and the destruction occurring around us. By creating something deliberately precarious with the intention of its destruction, she makes us question what it means to hold a work of art in our memory, and the impact of its existence, even if short-lived.

For example, in her 1967 sculpture Guardián, Vicuña gathered little sticks and debris from the beach, which she assembled into a fragile sculpture on the shoreline where the water met the sand, and then waited for the high tide to knock them down and erase them, completing the work. Through their fleeting nature, these fragile works become allegories for hope (Lynd 2005, 1593). Precarios allow her to see how it’s possible to create something beautiful which will live on, even if only through memory, while in exile, affirming the possibility of making art despite having no material or studio because of her displacement. Politically, her precarios also serve as a metaphor for resilience, as their impermanence illustrates how Chile’s acts of resistance would live on, even if only through memory. By crafting works intended to deteriorate, she invites viewers to question what it means to remember, preserve, and mourn. The memory of the work and its brief existence become a site of resistance, suggesting that what is ephemeral can still endure through its impact on our collective consciousness.

Cecilia Vicuña, Guardián, 1967

Expanding this metaphor, the California College of the Arts’ Wattis Institute Curatorial Fellow Jenni Crain prefaced an exhibit on Vicuña’s work by saying that Vicuña’s “precarios are full of pain” (2020, 1). As a testimony to the political resilience of precarios in the face of colonial and military violence, their ephemeral nature seeks to remember, honour and invoke what has disappeared, been destroyed or erased while simultaneously reminding us of our own existential condition and the importance of being present when considering the precarity of the nature of life (ibid.). Vicuña grounds her precarios in the natural world, as physical metaphors in space which create a “history ‘written’ in the memory of the land and the bodies of passersby” (Vicuña 2018, 83), Through this work she is able to connect to past and present communities whose pain is captured by their precarious nature, resonating with broader histories of pain, grief, and underground movements of poetic resistance. They seek to remind us of the violent and mobilizing conditions of our collective reality, urging us to challenge contemporary power structures through their ephemeral call to action, and act as reminders of our own precarious existence in the hopes of inspiring political resilience through the notion that our political actions take on a life of their own.

In contrast to this anti-monumental approach, her installation work with quipus often veers towards the monumental, with her large-scale installations taking over spaces such as London’s Tate Modern, where her Brain Forest Quipu hung from the roof of the Turbine Hall as a lamenting testimony to a disappearing world. These pale agglomerations of knotted cords, resembling dying vines and bleached-out trees, grieve the loss of traditional languages and the willful destruction of communities, their ways of life and cultures. She emulates this grief through a soundscape by Colombian composer Ricardo Gallo made up of string ensembles and choirs, field recordings and distant cries, which is in turn woven throughout the unspun wool strands over a system of hidden speakers around the hall and encircles the collection of reclaimed belongings and debris woven into its strands. The large frayed, knotted ropes and braided threads are full of mud-larked objects collected by members of London’s Latinx community from the Thames River, which she claims were rescued from the silt of past lives yet have become caught in the turbulence of the present (Searle 2022). This poetic relation draws comparisons between the lingering consequences of colonialism on Indigenous communities and its reclamation through her dedication to this practice of weaving and its potential for fostering collective social and historical memory. These works are unavoidable and use their monumentality as a memorial to what was lost and as a beacon of connection for the community and history she seeks to connect with and represent in these large-scale sculptural forms. Connecting the past and present through her revival of quipu weaving, Vicuña’s immersive quipus explore the nature of language and memory, the resilience of native people in the face of colonial repression, and Vicuña's own experiences living in exile.

Cecilia Vicuña, Brain Forest Quipu, 2022

Vicuña’s Decolonial Aesthetic: Deciphering the Line and the Thread

Throughout Vicuña’s work, her metaphor of weaving goes deeper than the physical knots of the quipu. In her decolonial deconstruction of the practice, she connects the idea of the poetic line and the woven thread. To her, the idea of the line and the thread are ubiquitous and often interchangeable, not only because of her dual identity as a visual and textile artist as well as a poet, but because thread and line are woven together to form a new worldview, as embodied through her arte precario (Díaz 2018, 175). Vicuña’s work is characterized by this openness and the sense of possibility, as the result of unraveling or unweaving language to be able to investigate its mechanisms and create something abstract with new ascribed meaning.

Her tendency to draw on old sources and mix her own words with ancient or sacred concepts conceived in the Quechua language (Rothenberg and Joris 1998) has been a central metaphor in her work and demonstrates her synthesis of the thread and line, which is deeply explored in her poetry. In her article Spinning the Common Thread, Lucy R. Lippard writes that if precarios are the common formal thread through Vicuña’s work, “the action of weaving itself is the aesthetic and spiritual thread that runs through all of Vicuña's cultural production.” Vicuña claims that the poem is “not speech, not in the earth, not on paper, but in the crossing and union of the three in the place that is not” (Vicuña 1997, 73). She engages weaving not only as an aesthetic and Indigenous spiritual thread across her work, but as a type of union between these concepts, which helps illustrate what is missing or has been forgotten. Weaving’s unifying power also helps show how disparate concepts may intertwine through her ontological and deconstructionist lens or help forge new connections at a conceptual level. Even the title of her collection, QUIPOem, represents the enmeshing of multiple realities, all at once referring to: poetry and quipus, quipus as poems, poems within quipus, the book as quipu, a biographical existence as quipu, time as quipu, etc. The unity Vicuña fosters between these two concepts produces a new aesthetic which both necessitates and creates a new language, where the line as thread and the thread as line results in the encounter of two aesthetic modes (Díaz 2018, 183). This practice is present across most of her works, and is exemplified in the following excerpt of her poem, which featured in her 1983 collection Precario/Precarious, ‘Word & Thread’:

Word is thread and the thread is language.

Non-linear body.

A line associated to other lines.

A word once written risks becoming linear,

but word and thread exist on another dimensional plane.

Vibratory forms in space and in time.

Acts of union and separation.

*

The word is silence and sound.

The thread, fullness and emptiness.

*

The weaver sees her fiber as the poet sees her word.

The thread feels the hand, as the word feels the tongue.

Structures of feeling in the double sense

of sensing and signifying,

the word and the thread feel our passing.

*

Is the word the conducting thread, or does thread

conduct the word-making?

Both lead to the centre of memory, a way of uniting

and connecting.

A word carries another word as thread searches for

thread.

A word is pregnant with other words and a thread

contains

other threads within its interior.

Metaphors in tension, the word and the thread

carry us beyond

threading and speaking, to what unites us, the

immortal fiber.

*

To speak is to thread and the thread weaves the

world. (Vicuña 1996)

This excerpt of the poem demonstrates Vicuña’s intertwining of these concepts and how she sees the line and thread as complementary metaphors. This matters because it shows us how her art and poetry can operate as tools to rethink the structures of meaning that have historically excluded or silenced marginalized voices. It’s useful to see how Vicuña herself articulates this relationship and sensibility, as it unpacks the metaphors at work across her many forms of expression. Her integrated aesthetic sensibility makes weaving and writing inseparable, revealing how form itself can act politically by making the connections between language, materiality, and cultural memory visible. By doing so, she uncovers the underlying mechanisms of how meaning is made, structured, and often controlled or limited. Her approach comes from a critical ideological transformation of basic literary and conceptual tools that she rethinks and reshapes to more accurately respond to political and historical violence in Chile, which has often been erased or overlooked in official histories (Díaz 2018, 177). In this sense, her conceptual art functions as a tool of reparation and invocation of other possible futures.

Vicuña’s recourse to Indigenous textile art and pre-Columbian aesthetics as a response to historical and political violence entails a closer consideration of how she employs notions of time, the past, memory, and loss; demonstrating why her work matters for contemporary conversations about memory, reparative justice, and decolonial aesthetics. Vicuña embraces traditional Andean notions of temporality where the past is not seen as something left behind, but as that which lies ahead (García 2021, 43). Her aesthetic project attempts to unearth what she sees as the origin of Chilean historical violence, and its impact on conceptions of collective memory, the past, and historical interpretations of resistance movements, where minority communities have often been portrayed as melancholic and associated with national allegories of failure (Díaz 2018, 176). Her work resists these neocolonial ideas of failure by highlighting Indigenous forms of resilience. By investigating how these projects embody Vicuña’s decolonial and feminist approach, we see not only the significance of her multidisciplinary practice but also how art can actively intervene in historical erasure and help us envision alternative futures. I believe this work matters because it demonstrates how creative practice is not just aesthetic, but also political and ethical, by offering a critical model for how to engage with history, memory, and social justice.

Temporality, Social Memory, and Resistance

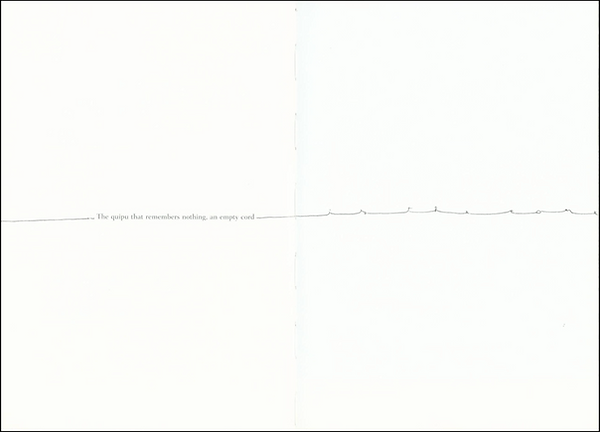

The first two pages of the Quipu Que No Recuerda Nada from QUIPOem 1997.

By embracing Andean ontologies in her decolonial and feminist practice, Vicuña engages memory and history as living, malleable entities capable of challenging colonial erasure and reclaiming Indigenous temporalities. Initially composed in 1965, but later rewritten for QUIPOem, Vicuña’s first precario and spatial work, entitled Quipu Que No Recuerda Nada or the Quipu that Remembers Nothing [artist translation], established the link between the theme of the precarious, the landscape, and Andean symbolism, which would later transcend and define her work. This early piece helped shape her political commentary, which eventually led to her self-imposed exile from Chile (Bachraty 2019), tying together nature, social action, and historical memory through her poetic engagement with the past. While its simplicity borders on abstract minimalism, drawing from Vicuña’s participation in conceptual art and her own aesthetic of precariousness as a critique of the self-reflexive model of modernism, the poem extends for three pages as a hand-drawn line which almost cuts straight across the page, as an ever-expanding and always connected thread which carries the potential for endless movement, where the thread symbolizes the present which “endures divides at each instant into two directions, one oriented and dilated toward the past, the other contracted, contracting toward the future” (Deleuze 1988, 52). In her act of deterritorialization, she resists and refuses the Western epistemological notion of time and limiting frameworks that seek to define her work, by embracing the Indigenous pluralist approach to her practice and to time, which puts the past, present and future in conversation. The quipu as an image and material object evokes a sense of meaning which is always inherently in flux, as Vicuña’s work connected the past and present, where the notion of the endless tying and retying of knots allows continuous marking and modification. On a literal level, as a system of writing the quipu provides opportunity for infinite inscription since what is ‘inscribed’ is never fixed (de Zegher 1997, 34). In the context of Quipu Que No Recuerda Nada, the not-remembering and capacity for open inscription offered by the form of the quipu synthesizes an attitude towards life, language, memory, and history in postcolonial Chile which embraces transformation as the basis for a new socialist collective culture by unifying the past and present, offering the possibility and potential for new futures.

In this 1997 ink representation of a quipu cord, the Quipu Que No Recuerda Nada, the inscription of the cord onto the page evokes Vicuña’s conception of the etymological relationship between language and string, or text and textile, specifically tying together how Vicuña conceptualizes written representation and threads of memory (Lynd 2005, 1593), across time. In her analysis of Vicuña’s poetic resistance and engagement of social memory, Hispanic and Luso-Brazilian Literature and Linguistics professor Dr. Juliet Lynd writes that:

The reinvented quipu does not so much suggest a desire to recuperate that lost code as it signals the emptiness of the traces of the forgotten and unknowable. Vicuna's quipu is an exact repetition of form that is conceptually entirely different; it can be read but never like the original. Unlike Gilles Deleuze's affirmation of the liberating potential of such recognition, there is a strain of nostalgia in Vicuna's early poem. [...] It is a relic that cannot remember the past but that in the present indicates a different way of representing memory. (2005, 1593)

Vicuna’s quipu making is thus transformed into a practice of memory-making and attempts to recover and reclaim “what time has erased” (Díaz 2018, 177). Yet even when that recovery is unattainable, she stakes a claim over the past through its recognition. The quipu remembers nothing, not because it cannot but because we cannot (Díaz 2018, 182). We don’t lack memory, but rather a way to remember; the past is ‘unactualized’ and contained within the thread, it merely remains inaccessible in our historical present. In her thesis Cecilia Vicuña’s Quipu-Making as a Theory of Time, Carolina Díaz theorizes that the quipu’s phenomenality and ability to trace its constitutive, original movements stand in the place of signification. What we lack instead is modality of interpretation, which is what Vicuña is trying to create in her unraveling of its symbols and patterns, and ascribed meanings. She meditates in the registers of pre-Columbian memory, the colonial past, and the postcolonial situation of Chile, as she works to create a new way of remembering the past and reclaiming its history, which is positive, affirmative, and transformative (2018, 183).

Her work entwines these three periods of time as she leans into Andean symbolism and makes a return to ancestral language, as she attempts to construct an alternative historical plot. She uses memory and loss to deconstruct and challenge our contemporary special imaginary, using this collective pain and grief experienced across all of these temporal windows at the hands of different Imperial systems through her woven mnemonic mechanisms. She hopes to forge a collective social consciousness in uniting and radicalizing current Indigenous and neocolonial social problems and memories as a knot that weaves together the pre-Columbian past and present Westernity.

In furthering her analysis of Vicuña’s work, Lynd claims that “memory is in fact constructed on what cannot be articulated” (2005, 1595) and that what was once forgotten cannot be faithfully remembered because it doesn’t exist anymore. In this framing, memory attempts to recover what time has erased, but it is an impossible project. She suggests Vicuña ties this idea of memory and what has been lost not only to language but to broader acts of colonialism, as visual remnants of precolonial history like quipus testify to a violence that has been erased but never forgotten. Her work in QUIPOem doesn’t essentialize Indigenous culture in opposition to colonial power but rather emphasizes the importance of reimagining and emphasizing Indigenous ontologies by inviting the reader to envision the interconnectedness between the self and others, or dichotomies like human and Earth (ibid.). The relationship between social memory and colonialism is imbued in the textuality of her work, and she takes the traditional craft of weaving and considers it a record of unspoken histories and lived experiences in the face of colonialism.

This piece embodies Vicuña’s interaction with space and time as an entwined continuum in which her poetry claims space. The Quipu Que No Recuerda Nada speaks to the contemporary authority of writing over the past, referring to the colonial rewriting and replacement of Indigenous accounts and testimonies. Angel Rama, a Uruguayan writer and literary critic, developed the concept of ‘transculturation’ to speak to these colonial acts of erasure and replacement. Rama builds off the work of Cuban writer Fernando Ortiz, who suggested that transculturation should be used to better express the process of transition from one culture to another because this does not only consist of acquiring another culture, which is what acculturation—the English word most commonly used in the context of colonial practices—implies, but the process also necessarily involves the loss or uprooting of a previous culture, or deculturation (Ortiz 1995, 102-3). Rama uses this lens of transculturation to explore the presence and consequences of colonial power inscribed in the written text, explaining how literacy has historically determined an individual or community’s access to power, how written documents ranging from property deeds and treaties to maps have imposed one order on another—European over Indigenous, the masculine over the feminine, written over visual—inscribing these social and power hierarchies in language itself through this process of transculturation (Lynd 2005, 1594). Vicuña steadily refutes and resists these processes of transculturation, which are tied to the disappearance of Indigenous cultures and languages, in her revival of these ancient and traditional techniques, which were long thought to be lost to memory. By shifting our understanding of colonialism, I believe Vicuña’s approach reveals the power of poetic resistance and refusal in action, showing how weaving and poetry operate as parallel processes of worldmaking that envision a future grounded in Indigenous epistemologies.

Conclusion: Reclamation and Future Possibilities

Cecilia Vicuña’s work is not fixed. It opens and prompts questions about the way we have constructed our own understandings of meaning by transforming words into living matter. She examines the ‘word’ on the edge of its poetic frontier and attempts to create meaningful connections which lie beyond its material boundaries. The making of her art is a ritual which engages with the construction of collective, socialist territory, carving out space to envision the future, and the deterritorialization of colonial projects and legacies. Vicuña's work, at its core, is a way of remembering. Both her personal history and story of suppressed Indigeneity and exile, as well as their place within a larger narrative of colonialism, threading them together and reclaiming what has been lost through her creative and community-building practices. Her work sits in the balance between ancient and contemporary forms, European and American origins, as well as “between the schemes of Indigenous languages and modern poetic inquiries” (Ramirez 1997, 70).

Within the broader Chilean political and artistic landscape, her work is deeply woven into the nation’s unfinished histories of violence, emerging not only as a response to the brutal repression of the Pinochet dictatorship but also the longer colonial project which erased Indigenous epistemologies and histories. Vicuña’s self-exile was a political act of dissent and survival; however, her distance from Chile, paradoxically, became the condition for her intimate and critical reimagining of it. While her work has been applauded internationally, it was not until Chile’s recent democratic transition and reckoning with memory and Indigeneity that Vicuña’s work received any proper recognition. When Chile’s Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes organized Vicuña’s first retrospective in 2023, Soñar el agua: A Retrospective of the Future, marking fifty years since the coup, the museum described the show as Chile’s debt to the artist. For artists and younger generations engaged in decolonial and feminist practices, Vicuña’s work resonates as a living archive of resistance, offering a vocabulary for thinking beyond Western materialism and patriarchal histories. Her invocation of the quipu, for instance, has become emblematic of a poetics of remembrance which connects Indigenous Andean cosmologies with contemporary struggles for ecological and social justice. This tension between the institutional reception of her work versus its resonance with younger generations mirrors Chile’s broader cultural division between the memory of the state and the memory of the people.

The threads of memory, meaning making, and the reinvestigation and reclamation of the past for our collective future transcend her work through the metaphor of weaving and unweaving at the core of her poetic resistance; she finds parallels in weaving and poetry through their rhythms and meter, and the way they open concepts up for questioning, have the potential to reframe our conceptions of the world, and challenge colonial power structures and legacies to change our ways of thinking and seeing the world. Her work forces us to interrogate and question what we gain materially from not framing the past and traditional Indigenous practices as unrecoverable but reclaimable, as we lay claim to its legacy in the territory of imagination. She pushes us to use the past to make sense of the decolonial present and also see how these threads of time are inseparable. We must pay homage to what is irretrievable and forever lost while also using it to find new ways to move forward and navigate our present, as Vicuña urges us to see time as a constant thread which can be woven together and unite us in our poetic resistance.

[1] These authors were selected for their expertise in art criticism, Latin American art and culture, and previous engagement with Vicuña’s work. QUIPOem/The Precarious was the first book-length publication in English featuring and analyzing Vicuña's work and was designed to be two books in one, with two different titles and front covers (Rubio 1999, 123).

[2] It’s important to note these feminist approaches have also been criticized for often veering into the Western feminist trope of silenced women as weavers, while remaining distant from conversations around the ‘material labor of poor women’ involved with the creation of textile arts across the world.

References

Alvergue, José Felipe. "The Material Etymologies of Cecilia Vicuña: Art, Sculpture, and Poetic Communities." Minnesota Review 82 (2014): 59-96. muse.jhu.edu/article/546568.

Bachraty, Dagmar. “Un Acto de Tejer y Destejer La Memoria. Los Quipus de Cecilia Vicuña y El Arte Actual.” H-ART. Revista de historia, teoría y crítica de arte, no. 5 (December 2019): 195–212. https://doi.org/10.25025/hart05.2019.10.

Crain, Jenni. “Whose Footsteps Are These? A Preface to Cecilia Vicuña.” CCA Wattis Institute for Contemporary Arts, September 28, 2020. https://wattis.org/browse-the-library/911/reading-lists-conversations-and-other-texts/whose-footsteps-are-these-a-preface-to-cecilia-vicua-a-by-jenni-crain.

Deleuze, Gilles. Bergsonism. Trans. Hugh Tomlinson and Barbara Habberjam. New York: Zone, 1988.

Díaz, Carolina. “Cecilia Vicuña’s Quipu-Making as a Theory of Time.” A Contracorriente: una revista de estudios latinoamericanos 16, no. 1 (2018): 174–202.

Fernando Ortiz, Cuban Counterpoint: Tobacco and Sugar, trans. Harriet de Onís. Durham: Duke University Press, 1995, 102–3. Translation of Fernando Ortiz, Contrapunteo cubano del tabaco y el azúcar (Havana: Jesús Montero, 1940).

Gubar, Susan. “‘The Blank Page’ and the Issues of Female Creativity.” Critical Inquiry 8, no. 2 (1981): 243–63. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1343162.

Howard, Rosaleen. “Spinning a Yarn: Landscape, Memory, and Discourse Structure in Quechua Narratives.” Narrative Threads: Accounting and Recounting in Andean Khipu. Eds. Gary Urton and Jeffrey Quilter. Austin: U of Texas P, 2002. 26-49. Print.

Jorquera, Carolina Castro. “We Are All Indigenous: Listening Our Ancient Thought.” Terremoto, July 17, 2017. https://terremoto.mx/en/revista/we-are-all-indigenous-listening-in-on-our-ancient-thought/.

Lippard, Lucy. “Spinning the Common Thread,” in de Zegher, M. Catherine (ed.) The Precarious: The Art and Poetry of Cecilia Vicuña. Hanover, NH: Wesleyan UP, 1997. 7-15.

Lynd, Juliet. Precarious Resistance: Weaving Opposition in the Poetry of Cecilia Vicuña. PMLA/Publications of the

Modern Language Association of America. 2005;120(5):1588-1607. https://doi.org/10.1632/003081205X73434.

Méndez-Ramírez, Hugo. “Cryptic Weaving,” in de Zegher, M. Catherine (ed.) The Precarious: The Art and Poetry of Cecilia Vicuña. Hanover, NH: Wesleyan UP, 1997. 59-71.

Museum Label for Cecilia Vicuña, Palabrarma: la palabra es el arma (Wordweapon: The Word Is the Weapon), AMAzone Palabrarmas, Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY.

Osman, Jena. “Is Poetry the News?: The Poethics of the Found Text.” Jacket Magazine, no. 32 (April 2007). http://jacketmagazine.com/32/p-osman.shtml.

Rothenberg, Jerome, and Pierre Joris. Poems for the Millennium: The University of California Book of Modern & Postmodern Poetry. Berkeley, California: University of California Press, 1998.

Rubio, Patricia. "The Precarious: The Art and Poetry of Cecilia Vicuna / QUIPOem." World Literature Today 73, no. 1 (Winter, 1999): 123-124. https://doi.org/10.2307/40154515.

Searle, Adrian. “Cecilia Vicuña Review – the Most Moving Tate Turbine Hall Installation for Years.” The Guardian, October 10, 2022. https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2022/oct/10/cecilia-vicunas-brain-forest-quipu-turbine-hall-review-tate-modern-london.

Soto, Christopher. “New and Selected Poems of Cecilia Vicuña.” Harvard Review, August 16, 2019. https://www.harvardreview.org/book-review/new-and-selected-poems-of-cecilia-vicuna/#:~:text=In%20an%20author’s%20note%20on,metaphors%20to%20come%20to%20light.%E2%80%9D.

Vicuña, Cecilia. Palabra e Hilo: Word & Thread. Translated by Rosa Alcalá. Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh: Morning Star Publications, 1996.

–––––. Precario/Precarious. New York: Tanam Press, 1983.

–––––. PALABRARmas. Capital Federal, República Argentina: El Imaginero, 1984.

–––––. QUIPOem / the art and poetry of Cecilia Vicuña. University Press of New England/Wesleyan University Press, 1998.

–––––. New and Selected Poems of Cecilia Vicuña. Edited by Rosa Acalá. Translated by Esther Allen, Suzanne Jill Levine, Edwin Morgan, Urayoán Noel, James O’Hern, Anne Twitty, Eliot Weinberger, Christopher Leland Winks, and Daniel Borzutzky. Berkeley, CA: Kelsey Street Press, 2018.

–––––. “Introduction.” Cecilia Vicuña. Accessed April 19, 2024. https://www.ceciliavicuna.com/introduction.

de Zegher M. Catherine. “Ouvrage: Knot a Not, Notes as Knots,” in de Zegher, M. Catherine (ed.) The Precarious: The Art and Poetry of Cecilia Vicuña. Hanover, NH: Wesleyan UP, 1997. 17-46.